Most investors know about diversification. It involves spreading your money across different assets to reduce the risk of investing. However, diversification is often done wrong – Investors often buy too few, too many, or sometimes the wrong types of assets in the pursuit of a diversified portfolio. So in this article let’s explore how many funds and shares you actually need to achieve a well diversified investment portfolio.

This article covers:

1. What is diversification?

2. How many funds do you need to invest in?

3. How many shares do you need to invest in?

1. What is diversification?

Investing involves risk. For example, if you invested all your money into one company and it went bust, you’d lose 100% of your money.

That’s where diversification comes in. Let’s say you invested your money across 20 companies – if one company went bust, you’d only lose 5% of your money. By spreading your money across multiple assets, you’ve reduced the impact of a poor performing investment on your overall wealth.

Diversification isn’t just about the quantity of assets you’re investing in. Here’s a couple of other important ways you can diversify an investment portfolio:

- By industry – Spreading your investment portfolio across companies operating in different industries (e.g. information technology, healthcare, real estate) in case investments in one industry perform badly.

- By geography – Spreading your portfolio across companies operating in different countries so that you’re not wiped out by an issue that affects a particular country.

Plus there’s many other ways to diversify your investments such as:

- By company characteristics – Spreading your portfolio across companies with different characteristics, for example across growth and dividend companies or small cap and large cap companies.

- By asset class – Involves investing across different asset classes such as shares, bonds, cash, and alternative investments (e.g. crypto or gold). We’d argue that this type of diversification isn’t critical – It’s perfectly fine to invest your entire portfolio into a single asset class such as shares or cash, as long as that asset class aligns with your investing goals and personal circumstances.

Overall, the key idea of diversification is to have your eggs spread across different baskets to reduce the risks of investing.

Is diversification for the ignorant?

Warren Buffett, a famous and successful investor, appears to be against diversification with the below quote:

Diversification is protection against ignorance. It makes little sense if you know what you are doing.

Buffett’s quote raises an important limitation of diversification – it goes two ways. While diversification minimises the negative impact of a poor investment, it also limits the positive impact of an outstanding investment. So if you know what you’re doing, why spread your money across multiple assets, when you can instead invest in a concentrated portfolio of quality assets and not have its returns diluted by average performing investments?

The problem is that in reality, most investors are ignorant and don’t know what they’re doing (us included!). Most investors lack the expertise or time to pick a concentrated portfolio of quality shares. And perhaps more importantly, most investors don’t have the risk tolerance to handle the volatility of owning a very small number of shares.

Therefore despite what Buffett suggests, most investors still need some form of diversification. In fact, Warren is a big proponent of owning broad market index funds like the S&P 500.

In my view, for most people, the best thing is to do is owning the S&P 500 index fund

Confusing right? So is less diversification or more diversification better? In sections 2 and 3 of this article, we discuss how many funds and shares you might need to be adequately diversified.

2. How many funds do you need to invest in?

The answer to how many funds you need depends on the types of funds you’re investing in:

Diversified funds

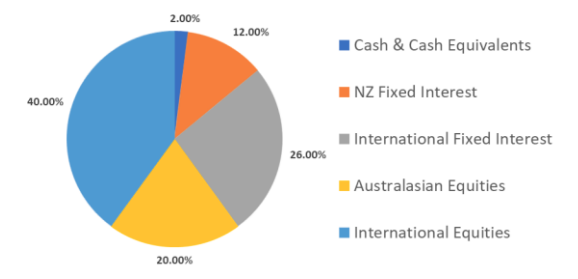

Diversified funds are funds that invest across multiple sectors. Most KiwiSaver funds fall under this category. Examples are:

- Kernel High Growth Fund

- Milford Active Growth Fund

- Foundation Series Balanced Fund

- Simplicity Conservative Fund

If you’re investing in a diversified fund, chances are it could be the only asset you need in your portfolio. That’s because these funds are diversified across many different ways:

- Quantity of assets held – Each diversified fund can hold hundreds and possibly thousands of assets. Therefore it’s highly unlikely for the value of such a fund to go to zero as that would require all of its underlying assets to go bust at the same time.

- Geographical diversification – These funds contain a mixture of local and international assets (which typically includes the US, Europe, Asia, and more).

- Sector diversification – They invest broadly into the market, containing assets operating in different sectors (e.g. Healthcare, Information Technology, Real Estate).

- Asset class diversification – In many cases diversified funds spread their investment across multiple asset classes. For example, a typical Balanced fund would invest in shares as well as bonds.

It may seem undiversified to hold just one fund, but these funds are designed to be a one-stop-shop for your investment needs. All you need to do is to pick one that aligns with your investing goals.

Further Reading:

– 4 steps to create an incredibly simple long-term investment portfolio

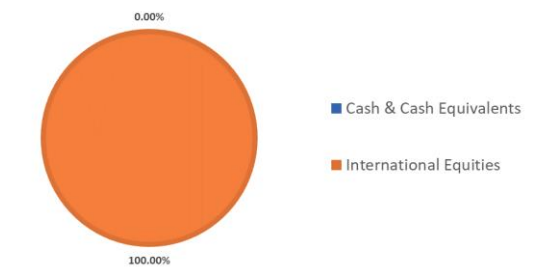

Single asset class funds

Single asset class funds are funds that invests in a single sector. For example:

- Kernel NZ 20 Fund (invests only in NZ shares)

- Smartshares US 500 ETF (invests only in international shares)

- Foundation Series Total World Fund (invests only in international shares)

In most cases investing in just one fund isn’t enough to provide an adequately diversified portfolio. For example:

- Kernel’s NZ 20 fund invests in NZ shares only, so provides no geographical diversification.

- Smartshares’ US 500 ETF invests in US shares only, so arguably provides insufficient global diversification.

- Foundation Series’ Total World Fund invests almost entirely into international shares, but has minimal exposure to NZ shares. While some investors are ok with not having NZ shares, it’s common to have some home bias because of the tax advantages that local shares have.

Therefore most investors will combine multiple single asset class funds funds to build their investment portfolio. There’s lots of ways to go about this such as:

- A two fund portfolio – One fund to invest in NZ shares, another for international shares. For example, investing in the Kernel NZ 20 Fund, plus the Kernel Global 100 Fund.

- A three fund portfolio – This tags a bond fund onto a two fund portfolio – suitable for more conservative investors,

Further Reading:

– 6 ways to build a long-term investment portfolio in New Zealand

Other considerations

More funds isn’t always better

Above we have shown that if you’re investing in single asset class funds, there’s diversification benefits to picking multiple funds. It may feel like more funds equals more diversification, in reality this often isn’t the case.

Firstly, more funds can end up concentrating your portfolio rather than diversifying it. For example:

- If you were investing in a global shares index fund, then added an S&P 500 index fund, you’d end up concentrating your portfolio towards the US (because global index funds already contain US shares). This might be a good thing if you intentionally wanted more exposure to US shares, but a bad thing if you’re looking for more diversification.

- If you were investing in a NZX 50 index fund, then added a NZ Property index fund, you’d end up concentrating your portfolio towards NZ property (because NZX 50 index funds already contain NZ property shares).

- Investing in the Smartshares US 500, Smartshares US Large Growth, and Smartshares US Large Value ETFs probably isn’t well diversified either as they all invest in US shares.

So the key to diversification here is to pick funds that invest in different underlying assets, while being aware of any overlapping underlying assets.

Further Reading:

– More funds = less diversification? Are you investing in too many funds?

Secondly, while things like geographical and industry diversification are important, there’s some areas that don’t need diversifying. For example, you don’t need to invest your money across different platforms/fund managers in case one of them goes bust – In most cases your investments are held by a custodian separate to your platform/fund manager, so your money won’t disappear if your platform shuts down.

Further Reading:

– What happens to your money if InvestNow or Sharesies go bust?

Where more funds might be useful

So far we’ve determined that a small number of funds is usually sufficient for an investment portfolio. However, there’s a number of valid scenarios where you might want to increase the number of funds you’re investing in:

Firstly, funds can be boring, especially if you’re just investing in one. The core-satellite portfolio is an interesting strategy which allows you to have some fun and invest in some more interesting assets without substantially increasing risk. Or they allow you to tilt your portfolio towards a specific area which you think will do well. It involves investing in a ordinary diversified or broad market fund to make up the core or majority of your portfolio, then adding more specialised assets (e.g. thematic funds or individual shares) to make up the satellite or minority of your portfolio.

Example of a core-satellite portfolio

John invests in the Kernel High Growth Fund. He’s a fan of electric vehicles and thinks that EV companies will do really well over the next decade. John starts to invest 5% of his portfolio in the Kernel Electric Vehicle Innovation Fund to get more exposure to EV related companies. It’s a satellite investment which won’t drastically increase the risk or complexity of his portfolio since the majority of his money is still invested in the High Growth Fund.

Secondly, there’s some cases where diversified funds might not be useful, for example, if you’re drawing down from your fund for retirement. A single diversified fund (e.g. one containing a mix of shares, bonds, and cash) often isn’t suitable retirees as they don’t allow you to choose which asset class to withdraw from – retiree would ideally want to drawdown the cash portion of their fund, leaving the bonds and shares to grow over the medium and long-term. So instead of investing into a diversified fund, it could be worth it for a retiree to split their money into different buckets (e.g. a cash fund for short-term spending, a bond fund for the medium-term, and a share fund for long-term growth) – a strategy we discuss further in the article below:

Further Reading:

– When’s a good time to sell or switch your investments?

3. How many shares do you need to invest in?

For those investing in individual shares, it’s a bit trickier to work out how many you need to build a well diversified portfolio.

The issue with too few or too many shares

The issue with too few shares

Having too few shares is risky, unless you are really skilled and are highly confident that your companies will perform really well over the lifetime of your investment. Some issues with too few shares are:

- Your portfolio is likely to be more concentrated – You’ll have fewer opportunities to spread your money across different industries and geographies.

- Higher volatility – The swings in the value of a company will have a large impact on the overall value of your portfolio (as you’ll have fewer assets in your portfolio to dilute the impact of those price movements).

- Every company is important – You might want to keep a close eye on them, since each one could make up a large part of your net worth.

The issue with too many shares

But having too many companies in your portfolio can also be problematic:

- It can be more complex – You’ll have more companies to research, keep up with, and perhaps calculate taxes on. That could result in a lower quality portfolio, as your efforts will be spread out on dealing with a large number of companies rather than concentrating on a few good ones.

- You might need to pay more fees – For example, Hatch charges a flat fee of $3 per transaction. Therefore a portfolio of 50 companies is going to be more expensive to buy into than a portfolio of just 10 shares.

- It dilutes the returns of your best performing companies – Your best performing companies won’t have much of a positive impact on your portfolio if your money is spread out too thinly.

- The benefits of diversification diminish when you add more companies – The more companies you add to a portfolio the less diversification benefit each additional company adds. For example, adding a 101st company to a portfolio of 100 companies doesn’t provide as much diversification benefit as adding and 11th company to a portfolio of 10.

So how many is right?

Too few shares is a bad thing, and too many shares is also a bad thing. It’s hard to find a definitive answer as to how many is right. Here’s what various studies and resources have to say:

- The Intelligent Investor, Benjamin Graham: 10-30 shares

- Investment Analysis And Portfolio Management, Frank Reilly and Keith Brown: 12-18 shares

- A Random Walk Down Wall Street, Burton Malkiel: 20 shares

- Haran Segram, Assistant Professor of Finance at New York University: 20-25 shares

- Some Studies of Variability of Returns on Investments in Common Stocks, Lawrence Fisher and James Lorie: 30 shares

Most seem to point to around 10-30 shares as the optimal number to have. That answer might not be helpful to some investors who are looking for a more specific number – is it better to have closer to 10 shares, or something closer to 30?

The right answer is personal

Ultimately the right number depends on factors such as your investing confidence, personal goals and preferences – The answer will likely be different for everyone! The structure of your wider portfolio also matters. For example, if you were already investing in a fund, that could reduce the number of individual shares you need.

We personally feel that 10 companies is on the low side – It makes it hard to be well diversified across different industries and geographies when you only have 10 companies to work with. On the other hand, 30 companies may be getting to the point of having too many – It can be hard to research and keep up with so many businesses, and you risk starting to fill your portfolio with average companies just to make up the numbers or just for the sake of diversification.

Perhaps a good place to start would be in the middle – Go with 20 shares and adjust that number up or down depending on your personal circumstances.

Does the amount of money you have matter?

Our opinion is that the amount of money you’re investing have shouldn’t have a major influence on how diversified your share portfolio needs to be. Diversification is a good practice to follow regardless of whether you have $500 or $500,000 invested. You could think about your portfolio in percentages rather than dollar terms. For example, you might decide to invest your portfolio across 20 shares, that’s 5% of your portfolio in each company. On a $500 portfolio, that’s $25 per company. On a $500,000 portfolio, that’s $25,000 per company.

Perhaps an even more important consideration

Perhaps an even more important factor than the quantity of shares you own, are the types of companies you’re invested in. While we’ve determined that ~20 shares is a good starting point for a diversified share portfolio, it wouldn’t be very diversified if you’d invested into 20 tech companies, 20 meme stocks, or 20 NZ companies. Investing in different (ideally somewhat uncorrelated) types of companies is what matters most in providing diversification, rather than the number of shares you have.

Conclusion

Diversification is an important concept for investors. It’s used to reduce the risk of investing by spreading your investment portfolio across different assets. However, diversification often isn’t an easy thing to get right. Too few assets and you might not adequately reduce the risk of your portfolio. Too many assets and your portfolio gets messy, and can start overlapping or diluting your holdings. Therefore a balanced approach to diversification is needed. So how many funds or shares do you need to achieve that balance?

For funds the answer is very small. One fund might be enough in the case of diversified funds, or even just 2-3 in the case of single asset class funds. That’s because a fund is a diversified asset in itself – And you don’t need to diversify what’s already diversified. Invest in too many of the, and you may end up with overlapping funds that unintentionally concentrate your portfolio.

For shares the answer is a bit more complicated. You don’t want too few, nor do you want too many. Most resources tend to suggest somewhere between 10-30 companies to provide a balance between adequately spreading your portfolio, and not having so many stocks that you make your portfolio too complex or start diluting it with lower quality companies.

But arguably it’s the types of funds or companies you’re investing in that matters more, rather than a question of quantity. For example, spreading your money across Contact Energy, Meridian Energy, and Genesis Energy probably isn’t the best way to go about diversifying your portfolio. It’s investing in assets that are at least somewhat uncorrelated that reduces risk, rather than the pure number of assets you own.

So overall there’s no perfect answer as to how many funds or shares you should have. But the decision of whether to invest in 15 companies or 20 companies, or whether to invest in 1 fund or 3 funds isn’t going to make or break your portfolio. So keep it simple and don’t overthink it.

Follow Money King NZ

Join over 7,500 subscribers for more investing content:

Disclaimer

The content of this article is based on Money King NZ’s opinion and should not be considered financial advice. The information should never be used without first assessing your own personal and financial situation, and conducting your own research. You may wish to consult with an authorised financial adviser before making any investment decisions.

As ever, nice article.

I’m curious if you’ve ever looked into 3 factor or 5 factor models, and specifically creating your own in nz using a collection of ETF’s? Benjamin Felix of ‘The Rationale investor’ (either youtube or podcast) does a great job of laying out the rationale. It is basically looking at research into the statistically non-correlated factors in the market, and the relevant risk adjusted returns you can get by investing following these factors. (note this is no way related to quant. day trading etc., this is choosing different diversified funds with a tilt towards high value, small cap, international etc.).

I find the subject fascinating, but don’t think we have the appropriate funds to do it in NZ currently. No worries if you haven’t had a look, but if you had, I’d be curious on whether you think it is feasible in NZ.

cheers!

p.s. he also has a nice video on the fallacy of dividend funds given that’s been coming up recently.

We watch most of Ben Felix’s videos but haven’t dug into the detail of a 3 or 5 factor model. It’s probably too complex for most investors (us included who prefer to keep things relatively simple). Potentially some of Smartshares’ ETFs could work in implementing such as model, like their US Small cap or value ETFs? Otherwise US domiciled ETFs provide plenty more options.

Ah the great and mysterious youtube algorithm! Bringing like-minded people together for good and bad! 🙂

Yeah I agree almost certainly more complicated than necessary (I’m pretty sure he makes that point in both the youtube and podcast editions of these models). My very cursory look at the NZ possibilities would suggest that the high fees associated with the us small cap, and value etfs, plus the lack of international options for either (and the tax implications of using foreign domiciled ETFs), would likely make it even less worthwhile in NZ. Though I haven’t bothered to look into it with any great depth, hence the question.

One of the interesting downsides to ‘boring/sensible/rationale’ index investing, is that you have nothing really to do for years and years at a time. Kind of a problem when you’re constantly reading about the subject. The desire to constantly tweak things is neither sensible, nor easy to ignore haha.

cheers

Thanks for another great article.

I’m slowly coming round to the idea that I have to whittle down my investments (spread across multiple funds and fund managers currently) in order to achieve that balance that you mention.

One thing that your article has awoken in me is the idea of investing in shares, alongside index funds; I am a product of a parent who was very good at picking shares and used those skills to put us through school! I remember the days of poring over the stocks/shares bit of the newspaper and the handwritten spreadsheets…

BW,

TR

Yes, like many things in investing the decision between funds vs shares isn’t an either/or choice. You can always invest in both! Seems like you’d be well positioned to be doing the latter 😀