Tax time is coming up! This can be one of the most daunting aspects of investing in foreign shares, given the special tax treatment on them. In this article we dive into the world of tax on foreign investments and discover some quirks around how Sharesies and Hatch treats your foreign investments. We also look at how estate tax might affect your US investments if you die. All of this in hopefully as plain English as possible!

This article is geared towards individuals who are New Zealand tax residents, and may apply differently to you depending on your personal circumstances. It should not be used as tax advice. If in doubt, seek advice from a tax professional.

This article covers:

1. When does FIF tax apply?

2. How do you calculate and pay FIF tax?

3. What are some quirks relating to FIF tax?

4. Is FIF tax avoidable?

5. Estate tax on US investments

6. Withholding tax on US partnership investments

Update (11 Dec 2022) – Added info on the upcoming withholding tax on US partnership investments

1. When does FIF tax apply?

If you invest in Foreign Investment Funds (FIFs) you’ll have to pay tax according to the FIF tax rules – this includes most shares and ETFs you buy from overseas markets like the US or UK. Here’s some common examples of what is a FIF, and what isn’t a FIF:

These are FIFs

- Shares listed on foreign sharemarkets e.g. US, Japan, UK, Hong Kong shares

- ETFs listed on foreign sharemarkets

- Some ASX-listed companies

- Most Australian Unit Trusts e.g. Vanguard funds on InvestNow

These aren’t FIFs

- Shares listed on the NZ sharemarket

- NZ domiciled funds and ETFs that invest in foreign markets e.g. Smartshares’ and Kernel’s international funds

- FIF exempt ASX-listed companies (most companies that pay Franking credits will fall under this category). You can check whether your ASX-listed company is FIF exempt or not on IRD’s website.

- KiwiSaver funds

- Other assets like foreign bank deposits, bonds, or cryptocurrency

For non-FIF investments you can check out our general tax article for details on how they’re taxed:

Further Reading:

– What taxes do you need to pay on your investments in New Zealand?

2. How do you calculate and pay FIF tax?

A. Determine how much you’ve invested in FIFs

The first thing you should do is to get an idea of the cost of your FIF investments. This is how much (in New Zealand Dollar terms) you originally paid for those investments. You should total up the cost of all your FIF investments, even if they’re spread across multiple platforms. This value is needed to determine what calculation methods you can use to calculate your FIF taxes.

This is different from market value which is how much your investments are worth according to their current share prices.

Example:

A couple of years ago Jack spent $40,000 NZD to buy Tesla shares on Hatch, and $2,000 NZD to buy Apple shares on Sharesies. His Tesla shares are now worth $80,000 NZD and his Apple shares are now worth $2,500 NZD.

The cost of Jack’s FIFs is $42,000 NZD. The market value of his FIFs is $82,500 NZD.

B. Know about the calculation methods

There are three main methods used to calculate your FIF taxes:

- Method 1 – De minimis exemption

- Method 2 – Fair Dividend Rate (FDR)

- Method 3 – Comparative Value (CV)

Here’s where the cost of your FIF investments calculated in step A comes in – If the cost of your FIF investments has remained less than $50,000 NZD throughout the entire tax year (running from 1 April to 31 March), you’re exempt from the FIF tax rules and will generally use method 1 (the de minimis exemption) to calculate your taxable income. It’s the simplest method and will usually result in the lowest amount of tax to pay.

Otherwise if you’ve held over $50,000 NZD in FIFs at any time of the year (even just for a day), you’ll need to choose between methods 2 or 3 (FDR and CV) to calculate your FIF taxable income. You can choose to use the method that results in the lowest taxable income for you.

Extra rules to keep in mind:

– The same method has to be applied for your entire FIF portfolio. You can’t use FDR for one asset, and CV for another.

– You can still use methods 2 and 3 if you’ve invested less than $50,000 in FIF investments. If you choose to do so, you must continue to use one of these methods for the next 4 tax years.

– There are other methods you can use to calculate FIF tax like Deemed Rate of Return (DRR) and Cost Method (CM), but these are much less common.

These methods can be daunting, but there’s are few resources that can help you such as reports provided by your investment platform, Sharesight (portfolio tracking tool which has comprehensive FIF reporting on their Expert plan), IRD’s online calculator, or an accountant. Otherwise read on for a more detailed look at the methods.

C. Calculate your FIF income

Method 1: De minimis exemption

This method taxes you on the dividends that you earn. To calculate your taxable income using this method, add up all the gross (before-tax) dividends you made from your FIFs during the tax year. Note these dividends have to be converted to NZ dollar amounts, which you can do so using the mid-month currency rates found here.

If your dividends plus “untaxed income” (income that you haven’t paid tax on yet like rental income or self-employed income) is less than $200 NZD, then you don’t have to declare this income and pay tax on it – that’s your FIF taxes all sorted!

Example 1:

Over the tax year Jack made $50 NZD in dividends from his Apple shares. He doesn’t have any untaxed income. Therefore Jack has no tax to pay on his FIFs, as he falls under the $200 threshold.

Example 2:

Vanessa invests in the Vanguard S&P 500 ETF. She made $300 NZD in dividends over the tax year. Therefore under the de minimis exemption Vanessa’s taxable income on her FIFs is $300.

Advantages of the de minimis exemption:

- Easy to calculate – the exemption is designed to make it easier for those with smaller portfolios to comply with their FIF tax obligations.

- If you’ve earned under $200 NZD in dividends plus other income, this is tax-free.

- Capital gains generally don’t end up being taxed under this method. This is great if you’ve invested in shares which pay little or no dividends but have potential for high capital growth.

Disadvantages of the de minimis exemption:

- Could result in high taxes if you have dividend-heavy portfolio.

- You may still be liable for capital gains tax when you sell your shares, if you bought them with the intention of selling them in the short-term to make a profit.

- Can’t be used for larger portfolios.

Method 2: Fair Dividend Rate (FDR)

This method taxes you on the assumption that you’ve earned a 5% dividend on your FIFs. To calculate your taxable income using this method, take the market value of your FIF investments (in NZD terms) at 1 April (the start of the tax year). Then multiply that amount by 5% or 0.05.

If you bought and then sold the same asset within the year, you’ll need to add a quick sale adjustment to your taxable income calculation. The quick sale adjustment is calculated using the lesser of these two methods:

- Peak Holding method

- Actual Gain

More detail on these quick sale adjustment methods can be found on page 15 of IRD’s Guide to FIFs.

Example:

The market value of Jack’s FIFs at the start of the year was $82,500 NZD. He invested a further $20,000 NZD into his FIFs throughout the year. He made no quick sales during the year.

Under the FDR method, Jack’s taxable income is $82,500 x 5% = $4,125.

Advantages of the FDR method:

- Relatively easy to calculate.

- Your taxable income is capped at 5%. For example, even if you made a total return (capital growth + dividends) of 10% you’d be taxed as if you had made a return of just 5%.

- Taxable income is calculated based on your start of year investment value. So any contributions you make to your FIFs throughout the year are effectively tax-free.

Disadvantages of the FDR method:

- If your total returns are less than 5% for the year, using this method would result in you effectively overpaying tax.

- Any FIFs you sold off during the year still get taxed, since it’s calculated on your start of year investments.

- The quick sale adjustment can greatly increase the complexity of this method.

Method 3: Comparative Value (CV)

This method taxes you on the actual increase in the value of your investments. To calculate your taxable income using this method you need two values:

- Value 1 – The opening market value of your FIFs (on 1 April at the start of the tax year) + costs (cost of buying new units in your FIFs)

- Value 2 – The closing market value of your FIFs (on 31 March at the end of the tax year) + gains (dividends and sale proceeds)

Then take value 2 and subtract value 1 to calculate your taxable income. If the result is negative, that means you’ve made a loss for the year and your FIF taxable income is $0 (as losses can’t be used to offset your other taxable income).

Example:

The market value of Jack’s FIFs at the start of the year was $82,500 NZD. He invested a further $20,000 NZD into his FIFs throughout the year. His value 1 is $82,500 + $20,000 = $102,500

The market value of Jack’s FIFs at the end of the year was $110,000 NZD. He made $50 NZD in dividends. His value 2 is $110,000 + $50 = $110,050

Under the CV method, Jack’s taxable income is $110,050 – $102,500 = $7,550

Advantages of the CV method:

- Will result in less (or even zero) taxable income when your total returns are negative or very low.

Disadvantages of the CV method:

- The most complex method to use.

- Results in paying tax on your unrealised capital gains + dividends, so doesn’t work out well during high return years.

Further Reading:

– Basic FIF Tax Calculator

D. Pay your FIF tax liability

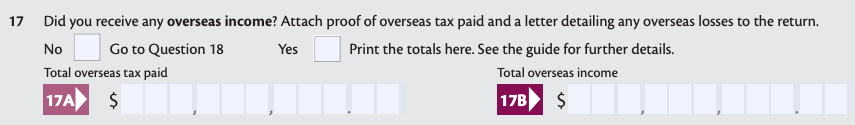

If you have FIF taxable income you’ll need to declare it on your IR3 – Individual Tax Return. This tax return has to be completed by 7 July each year. On the IR3 form you’d put your FIF income in the Overseas income (17B) field:

So how much tax do you have to pay on this income? FIF income is taxed at your marginal tax rate, according to the below table:

| Income | Tax rate |

| $0 – $14,000 | 10.5% |

| $14,001 – $48,000 | 17.5% |

| $48,001 – $70,000 | 30% |

| $70,001 – $180,000 | 33% |

| $180,001 or more | 39% |

Example:

Vanessa has calculated her FIF taxable income to be $300 NZD. Her income from all other sources (like her salary) is $80,000. Therefore she’ll pay tax on her FIF income at 33%. That gives her a tax liability on her FIFs of $99.

Don’t worry if you don’t know your marginal tax rate, as IRD will calculate this for you when you submit your tax return.

Overseas withholding tax

Any overseas tax you’ve already paid should be declared in the Total overseas tax paid (17A) field of your IR3. This will usually be the withholding tax you pay to a foreign government when you receive overseas dividends. For example, if you receive dividends from Apple shares, you would’ve paid a 15% withholding tax to the US government. This amount can usually be claimed as a foreign tax credit, reducing your overall NZ tax liability.

FIF disclosure statements

In very limited cases you may need to submit a FDR disclosure form or CV disclosure form with your tax return. This will be the case if you use the FDR or CV methods and a company or fund you own is incorporated in a country that New Zealand doesn’t have a tax treaty with.

3. What are some quirks relating to FIF tax?

A few platforms and assets have quirks to watch out for when dealing with FIF taxes:

Sharesies

Sharesies automatically pays FIF tax for you on the assumption that their customers are taxed under the de minimis exemption by deducting 33% tax from your overseas dividends. The implications of this are:

- If you’re a de minimis investor on the 33% marginal tax rate, this is great as your FIF tax obligations are automatically taken care of for you.

- If you’re a de minimis investor on another tax rate, this will result in you overpaying or underpaying tax. However, this under or overpayment will be corrected when the IRD issues tax refunds or bills after the end of the tax year.

- If you have a large portfolio and the de minimis exemption doesn’t apply to you, then Sharesies’ tax treatment of your FIFs is incorrect. Sharesies recommends you seek professional tax advice if this is the case.

In addition, the way Sharesies treats FIF tax may be financially disadvantageous:

- They deduct tax from you upfront when you receive a dividend, resulting in less cash to reinvest. On other platforms FIF tax is paid after the end of the tax year, so can be reinvested to earn a return in the meantime.

- They deduct tax from you even if your overseas dividends (plus other income) are below the $200 threshold. You normally wouldn’t be taxed in this case.

Hatch

Any money you deposit into Hatch is converted to USD and held in DARXX – a cash fund in which you can earn interest from your USD cash. DARXX is considered to be a FIF, which results in a couple of quirks. Take the following scenarios as examples:

- You deposit $60,000 NZD into Hatch but only invest $40,000 NZD of it into shares.

- You buy $40,000 NZD of Tesla shares. Later on you sell them for $80,000 NZD.

Both scenarios would normally allow you to apply the de minimis exemption, given the cost of your FIFs are less than $50,000 NZD. However because Hatch stores your USD cash in a FIF, both of the above scenarios would result in over $50,000 NZD being invested in FIFs, requiring you to use the FDR or CV methods to calculate your taxes.

Australian Unit Trusts (AUTs)

When you use the de minimis exemption, any capital gains you make would usually not be taxed. The problem with AUTs (like Vanguard’s International Shares Select Exclusions Index Fund) is that they have to pay out any realised capital gains as dividends. This effectively results in you having to pay tax on capital gains, whereas this wouldn’t happen on non-AUT funds.

Cash and Bond ETFs

While individual bank deposits and bonds aren’t considered FIFs, investing in overseas cash and bonds through an ETF (including Hatch’s DARXX fund) are counted as FIFs. This could result in suboptimal tax treatment for them – Say you had a portfolio of overseas share and bond ETFs, and you chose the FDR method to calculate your FIF taxes. The FDR method would calculate tax on your shares and bonds at the same 5% rate, even though your bonds would’ve likely delivered a smaller return than your shares!

4. Is FIF tax avoidable?

We often see people wanting to avoid FIF tax – usually due to the perceived complexity of the FIF tax regime. This is especially the case with investors who are getting close to investing $50,000 NZD overseas and are wanting to avoid having to use the more complicated FDR or CV methods. One way investors attempt to avoid FIF tax is to invest in locally domiciled funds, for example, the Smartshares Total World or AMP All Country Global Shares funds, which both invest in overseas shares, but aren’t considered to be FIFs.

Indirect FIF tax

Unfortunately FIF tax is unavoidable even if you use a NZ domiciled fund to invest in overseas assets. Given these funds invest in FIFs themselves, they still need to pay FIF tax to the NZ government – tax which is then passed onto you, the investor. Therefore while you’re not paying FIF tax directly to the IRD, you still end up paying it indirectly.

In fact this indirect FIF tax may leave you worse off than direct FIF tax. NZ domiciled funds always use the FDR method to calculate their FIF taxes – they have no option to apply the de minimis exemption or select the CV method in low return years. Given it’s reasonable to expect low or negative returns every few years (where the CV method is advantageous), this is a major disadvantage of these funds.

However, this disadvantage is offset as the maximum your tax rate on these funds is 28% (good for those in the 30%/33%/39% tax brackets), and because of the simplicity of not having to deal with FIF taxes yourself (potentially saving accounting costs). In addition, investing in NZ domiciled funds will usually save you from paying brokerage and foreign exchange fees.

Further Reading:

– Smartshares US 500 (USF) vs Vanguard S&P 500 (VOO) – Which ETF is better?

Should you change your investing habits?

FIF tax can be a pain, and in many cases work as an effective tax on your capital gains (which usually aren’t taxable in NZ). The below table shows the estimated annual tax impact on various investment products, where international shares are clearly taxed more heavily regardless of whether you use NZ domiciled funds or FIFs to access them:

| Investment product | Estimated annual tax |

| NZ direct shares e.g. Auckland Airport shares | 0.42% |

| NZ ETF or unlisted PIE investing in NZ shares e.g. Smartshares S&P/NZX 50 ETF | 0.26% |

| NZ unlisted PIE investing in international shares e.g. Kernel Global 100 Fund | 1.40% |

| NZ ETF investing in international shares e.g. Smartshares Total World ETF | 1.78% |

| Australian direct shares e.g. Woolworths shares | 0.82% |

| US direct shares e.g. Apple shares | 1.15% |

| US ETF investing in US shares e.g. Vanguard S&P 500 ETF | 1.15% |

| US ETF investing in international shares e.g. Vanguard Total World Stock ETF | 1.52% |

So to completely avoid the higher impact of FIF tax you could just invest in NZ shares which are generally capital gains free, and whose dividends often have imputation credits (heavily reducing the tax payable on them). After all, one of the intentions of the FIF tax regime is to encourage investment in NZ companies.

In addition, you could invest directly in Australian shares, which also have relatively friendly tax treatment, apart from the fact Kiwi investors can’t claim the franking (imputation) credits attached to Australian dividends.

But despite the higher tax impact on FIFs, it’s not worth changing your investing habits in response. The diversification you get from investing in overseas assets is worth it, and an important aspect of building an investment portfolio:

- Geographical diversification – It’s important to spread your money across different countries, especially when NZ and Australia make up just a tiny fraction of global sharemarkets

- Sector diversification – NZ and Australian sharemarkets have a heavy weighting towards certain sectors (healthcare, industrials, utilities in the case of NZ, and financials, resources for the Aussie market). Investing in other countries allows you to get exposure to industries that are underrepresented in the NZ and Australian market like technology and consumer staples.

Further Reading:

– Guide to Taxation of Foreign Equities for New Zealand residents (Kernel & MyFiduciary)

5. Estate tax on US investments

When you die, your investments are inherited by your family or who you specify on your will. One of our readers Neal pointed out to us that the United States has an estate tax where you could be taxed up to 40% on your US investments upon your death! This estate tax applies when:

- You’re a foreign individual investor (this includes New Zealanders)

- You have over $60,000 USD (~$88,000 NZD) invested in US shares

- Your country doesn’t have an Estate Tax Treaty with the US (this includes New Zealand)

The potential to be charged up to 40% estate tax raises a strong case for keeping your US domiciled investments under $60,000 USD, and/or using NZ domiciled funds (like the Smartshares US 500 ETF) to invest in US shares, in order to avoid that tax altogether.

We were interested in what NZ brokers like Sharesies and Hatch had to say about this tax as they’ve never highlighted this topic before, so we reached out to both of them. Sharesies haven’t gotten back to us yet apart from saying they’re confirming some details, while Hatch never responded to us. However, we did find the following comment in Hatch’s Facebook Group regarding estate tax:

We’ve spoken to a number of tax accountants and experts in this area and they’ve never seen a case where the US comes after an investor’s assets in this capacity. While we can’t promise this won’t happen, it would be unusual. Shares are held in “street name” which means that the broker is linked to the share – held on behalf of you. This would also make it difficult for the US government to do so.

That said, it’s important to weigh up the risks and potential of the government coming after estate tax.

Hatch

In summary, Hatch’s position is that it’s unlikely (but still a possibility) that the US government will chase your investments for estate tax. So it’s not 100% clear whether estate tax will actually apply in practice. But given this tax rule still exists in theory, we think it’s still an important consideration for Kiwis investing directly in US shares.

6. Withholding tax on US partnership investments

New US tax rules are coming into force on 1 January 2023, which will result in non-US taxpayers being hit with a 10% withholding tax on US partnership investments. Don’t freak out – this rule does not apply to all US investments like Apple, Microsoft, Tesla, and S&P 500 ETFs, but only to a small number of investments structured as a publicly traded partnership, which have different tax rules over in the US. Sharesies has provided a list of affected investments here, and Interactive Brokers has provided a list here.

If you do hold any of these investments, a 10% withholding tax will apply to your sale proceeds when you sell the asset, regardless of whether you made a profit or loss on the investment. For example, if you sold your units in the United States Oil Fund (USO) and received $1,000 USD for the sale, a $100 USD withholding tax would apply.

Conclusion

Tax on foreign investments is certainly not as friendly as tax on NZ investments. But the good news is that if you’ve invested less than $50,000 in FIFs, the de minimis exemption makes things relatively simple (and even tax-free if your dividends plus untaxed income is under $200).

But for all other investors, tax on international investments can be a pain. Firstly the amount of tax payable through the FIF regime will generally be higher than tax on local shares. Secondly the effort needed (either from you or an accountant) to calculate your FIF taxes can be significant. Thirdly, you may also need to consider the risk of paying 40% in estate tax on US shares upon your death.

Unfortunately FIF taxes aren’t avoidable by investing in NZ domiciled funds (like Smartshares’ US 500 ETF, or Kernel’s Global 100 Fund). Local funds investing in foreign companies will still incur FIF tax and pass that onto their investors – essentially an indirect FIF tax. But these are still friendly options for investing internationally as they take care of the FIF calculations and paperwork for you.

Despite the disadvantages relating to tax on foreign investments, we believe they’re well worth it for the diversification you’ll get from investing beyond New Zealand.

Thanks to Neal for bringing the topic of estate tax to our attention.

Follow Money King NZ

Join over 7,500 subscribers for more investing content:

Disclaimer

The content of this article is based on Money King NZ’s opinion and should not be considered financial advice. The information should never be used without first assessing your own personal and financial situation, and conducting your own research. You may wish to consult with an authorised financial adviser before making any investment decisions.

What happens to early NZ Rocket Lab investors (with more than $50k invested)? E.g. let’s say an NZ investor invests in Rocket Labs when the company is in NZ, as it’s a private company there’s limited opportunity to sell, then it lists in US for several billion. What’s the “cost” value? Is it the private valuation as arrived at by venture capitalists or the value it lists for on the NASDAQ (assuming both values were arrived at in the same year, but the NASDAQ one is 3x higher)?

The article mentions how investment in Australian equity is slightly more friendly than other FIF’s. Could you elaborate? I have several FIF’s in Australian equity that exceed the 50k cap and would be keen to learn more. As you note, I don’t get to make use of the Franking credits . Ps thank you for a very well written article

Hi Marlon, many ASX listed companies are FIF exempt as per IRD’s page here: https://www.ird.govt.nz/income-tax/income-tax-for-businesses-and-organisations/types-of-business-income/foreign-investment-funds-fifs/foreign-investment-fund-rules-exemptions/foreign-investment-fund-australian-listed-share-exemption-tool

If you hold a FIF exempt ASX listed company, it is taxed as if it were a NZ equity – that is generally only dividends are taxable (with the exception that franking credits can’t be utilised).

What rules apply if dividendsare re-invested?

The same rules apply whether or not dividends are reinvested. It’s considered income either way.

Do FIF rules still apply on unlisted overseas shares? Ie privately held companies/startups that may be many years away from going public.

Yes, unlisted companies can also be considered as FIFs

Can we select method each year. Like in 2020 Tax year CV Method got loss and thus no income to dsclose. In 2021 FDR is giving lowest income of 10,000. Can we change method selection each year

Yes, you can change method each year as long as you use the same method across all your FIF holdings that year.

US estate tax only applied to estates worth over US$12+ million. The threshold rose from about US$5M in 2017 to the 2022 level. If over the threshold, you pay 40% in tax. Below, you pay nothing.

We understand that $12 million threshold is for US citizens and domiciliaries, while non-US residents have a threshold of just $60,000.

Thanks for a great article. Is the FIF taxable income in addition to the dividends received?

For example, if my dividend income received from these FIF is $3k over a tax year, and at year-end, the lower of CV or FDR suggests a taxable income of $2k with investment costing above $50k – is the overall taxable income $5k or $2k?

Thanks

Tax on dividends are already captured within the FDR and CV method calculations, so if you choose to use those calculations there is no further tax on the dividends.In your example overall taxable income should be $2k

great thank you – really appreciate you taking the time to respond, have a great evening

Do brokers withhold any tax on capital gains from the sale of US ETF shares (ie. VOO through Interactive Brokers) by a New Zealand tax-resident (signed W8-form)? If not, does that mean that no tax needs to be paid to the USA for these capital gains (specifically for de minis).

No, it’s up to the individual to work out whether capital gains tax applies to your sale, and pay to the IRD if required.

Thanks for a great article. Is brokerage or transaction fee needs to be deducted for calculating capital gains from stock buy & sale?

Generally any capital gains would be calculated net of brokerage fees.

Does FIF “on paper” profit / gain count as / towards your actual income on a tax return? This seems bizarre as any profit or gain is on paper only and if no shares are sold then the individual has received no actual income whatsoever.

Yes, for example using the CV method takes into account your paper gains. So you are effectively taxed on non-realised gains. Certainly is a downside of investing in FIF versus non-FIF assets.

I own a NZ limited company which invested 40,000 NZD into foreign shares does FIF apply to non natural person? Thank you

Hi if you have a loss using FDR and CV what do you have show in your IR3 and IR1261 tax return? I’m confused with a comment that a letter is needed?

Sorry if I missed it, in the example table why is the total world ETF effectively paying more tax than the US shares?

Would appreciate some insight into the tax treatment of NZ unlisted funds which invest in international bonds.

Thanks

You don’t mention Americans living in NZ and invested in the US stock market prior to the FIF law changes. They couldn’t invest in NZ because of the punitive American PFIC tax on foreign funds. When the law changed they couldn’t simply sell up and bring their money home to NZ because of the significant capital gains tax they would owe to the US government if they did so. They find themselves trapped if their life savings investment exceeded $50,000.

It is actually possible to have a significant reduction in value in USD using the CV method, only to have that translate to a significant increase in value when the opening and closing values have been converted to NZD. They can find themselves paying tax on the high NZD amount, even when they have not realised any gain and have lost significant value.

It looks like when using Hatch, if someone deposits a lumpsum and buys individual shares/ETF at a total investment cost of 40K NZD for instance, then keeps the shares/ETF for the long term, and eventually sells them when their market value is above the 50K NZD threshold, they would still have to pay FIF tax as the balance before withdrawal would be held in a DARXX account (triggering a FIF tax) when the shares/ETF are sold.

Is there a platform you’re aware of that stores the balance outside of a fund that’s considered a FIF?

Cheers

New subscriber

We’re not aware of any other NZ platform that stores cash balances the same way as Hatch

This doesn’t make sense. The FIF threshold is based on the amount of money you invested – ie the COST of your investments. If you invest less than $50,000 NZD and the share market value grows well beyond that, you are still NOT under FIF. (You pay tax on dividends and interest) But if you invest more than $50,000 NZD (ie you pay more than $50K in total) no matter how much or little the market value grows, you are still under FIF. Even if the market value goes below $50K. At least that’s how I understand it and how it has beed explained to me

It’s trickier than you think. My understanding is if you’re using a platform like Hatch that stores your available balance on a money market fund like DARXX, any time your investment cost OR the available balance on your account goes above $50,000 NZD, you will be under FIF for that year. E.g. Let’s say your total investment COST is $20,000 NZD and its market value grows to become $100,000 NZD in ten years. If you now sell all your investments, the $100,000 NZD (less brokerage fees) goes straight to your available balance on Hatch, which is where you can withdraw the money from, but since the available balance is treated as an investment, this will essentially trigger a FIF tax.

Seems odd, right?

From Hatch: “Your available balance is treated as an investment for FIF purposes and counts towards this $50,000 NZD investment cost.”

https://help.hatchinvest.nz/en/articles/4620308-what-is-a-money-market-fund

@Money King NZ – do you agree?

Kathy is correct in saying that the FIF threshold is based on cost of investments. However, your interpretation of FIF tax treatment on Hatch is correct.

Using your example, if you buy $20k worth of stock, then it goes up to $100k and you sell, this normally would not be taxed under FIF given the cost is still $20k.

However, with that same scenario on Hatch, you would sell $100k of stock, then the platform immediately buys $100k worth of stock in the DARXX money market fund. Now the cost of your investments in FIFs is $100k, so you’re no longer exempt from FIF tax.

Good God! So being with Hatch FORCES you into an FIF arrangement, and the tax on “deemed income” that FIF involves!

FIF came in at the same time as Kiwisaver (and a $2,000 gift from government if you joined) It was intended to bring NZD invested in foreign shares home. Now Hatch automatically invests your cash from the sale of shares into a foreign fund?? That’s really nuts.

Meanwhile, if you are a dual US/NZ citizen, you can’t invest in Kiwisaver (or any funds considered “foreign” by the US) without facing a punitive PFIC tax from the US. There is NO place where a dual US/NZ can invest without severe tax consequences ever since FIF came into effect. That not only disadvantages dual US/NZ citizens (who have to report and pay tax to the US no matter where else in the world they are tax residents), it is a barrier against wealthy capital venture individuals and technology experts from moving to NZ to support growth in the tech sector here. Such people are recommending tweaking the FIF law to give individuals the option of paying a capital gains tax on foreign investments rather than FIF tax. A capital gains tax on actual income makes so much more sense than FIF.

I’m worried I might receive over $200 in dividends with the fluctuation USD.NZD

If I sell some US shares at my average buy price then that shouldn’t count as “untaxed income” right?

Thanks, this is a great article! I was hoping to check my understanding of one point.

If my family members (wife and children) have all purchased FIF investments (e.g. US ETF/US listed individual shares) at below the NZD $50,000 de minimis threshold each (say, at a purchase price of $48,000 for each person), am I right to think that each of us could also then purchase as much Kernel Wealth international funds (e.g. Kernel S&P 500) as we wanted (say another $50,000 each) and still not have crossed the $50,000 de minimis threshold because our investments in the international Kernel wealth funds wouldn’t be categorised as an investment in a FIF?

That is correct, you would still have $48,000 NZD each in FIFs

What happens if you put in 100K in 2024 financial year, value is still 100K at start of 2025 financial year, and you sell in 2025 financial year?

Whoops – if you sell at, for example, 150K?

Great article and very useful for me. One question not covered and not clear on the IRD web site is what exchange rate to use or what options (actual day rate, mid month, end month, or rolling annual average) can one use for

1) Calculating the value of the FIF if one buys the shares using an overseas broker say on the 11th of the month

2) Calculating the value of the dividends

I understand that “The income tax treaty in effect between the United States and New Zealand governments overrides the income tax law of each country. It is based on the OECD model tax treaty with some variations and was updated in 2011” (NZ/US Tax Specialists)

Since the FIF rules came in decades after the treaty was signed, wouldn’t that exempt US citizens living in NZ from FIF, given that FIF “income” is taxed by NZ as US income yet is not included in the US tax code as “income”?

Is there any tax advantage to creating a Company or Trust and gifting your shares to it?

What about the same above scenario, and then moving to Australia, does that give reduced taxation at least until the shares are sold?