Selling is important part of investing. It’s how you realise the profits on your investments and how you get your money out to use on your goals. Unfortunately it’s harder to know when to sell an investment than knowing when to buy, plus it doesn’t tend to be a topic covered much by investment content creators. In addition, knowing when’s a good time to switch from one fund to another can be another point of confusion for investors. So in this article we’ll explore some of the factors you might want to consider when making the decision to sell or switch your investments.

This article covers:

1. When should you sell an investment?

2. When should you switch funds?

3. Tools, strategies, and considerations when selling your investments

1. When should you sell an investment?

Knowing when to sell your investments is arguably harder than knowing when to buy. There’s no golden rule to tell you when’s the right time to sell, however we can look at some of the good reasons for selling an investment as well as some of the bad ones:

Good reasons to sell an investment

Your personal circumstances or goals have changed

Ideally the investments you hold should contribute to your financial goals and be aligned with your personal circumstances including:

- Your investment objectives – Why you’re investing in the first place.

- Your risk tolerance – Your willingness/ability to handle the risk and volatility relating to your investments.

- Your personal preferences – Things like your ethical views and the style of investing you prefer.

Further Reading:

– How to invest $1k/$10k/$100k in New Zealand

If any of the above factors change, chances are some or all of your investments will no longer be aligned with you, providing a strong reason to sell off those investments. For example:

- If your investment objectives have changed, then you may have to sell off investments that don’t align with your new goals.

- If your risk tolerance has decreased, then you may want to sell off some higher risk investments to reduce your portfolio’s volatility.

- If your ethical views have changed, then you may look to sell any assets that go against those views.

Essentially people and their circumstances change – so your portfolio should change along with you.

Your investment’s fundamentals have changed

When buying into an investment, there’ll usually be a number of reasons which attracted you to invest in that asset in the first place. For example:

- You may like a company for its products/services and its growth prospects.

- You may like a fund for its low fees, tax efficiency, and broad diversification.

If the reasons that made your investment attractive in the first place no longer apply, that may provide another strong case to sell off your investment. Take the following hypothetical scenarios as examples:

- You originally invested into a company because of the growth prospects relating to a new product they’re releasing. But that new product turned out to be a flop.

- You invested into a company as it had reliable and steadily growing profits. But some external factor like a pandemic or regulatory change had an adverse impact on the company’s profitability.

- You invested in an index fund because of its low fees, only for them to increase the fees later on.

Companies and investment products change, and not always for the better. Ask yourself whether you’d buy that same asset today, and if not, that may be good reason to sell and seek better opportunities to put your money.

To rebalance your portfolio

Over time your portfolio’s asset allocation may drift away from what it needs to be. Say you have an investment portfolio that’s 90% invested into shares and 10% invested into bonds. The following factors may require you to sell off some of your investments to rebalance your portfolio:

- Performance differences – Different assets perform in different ways, for example shares tend to perform better than bonds over the long-term. This may result in your portfolio becoming overweight in one asset (e.g. shares), and underweight in another (e.g. bonds).

- Time – As you get closer to goals you’ll need to adjust your asset allocation away from shares and into bonds/cash.

In these cases you may decide to sell off some of your investments to get your portfolio back to its ideal asset allocation.

Not so good reasons to sell an investment

Because the price went down

Financial markets are volatile by nature, so price movements alone are not a good reason to sell your investments. Selling an investment just because the price went down could result in you locking in your losses or selling off a perfectly good asset for a bad price. Assuming you’re holding onto quality assets, the best course of action is to hold on to them as there’s a good chance they’ll recover from any market downturns.

However, if your investment’s price went down AND its fundamentals have changed, then that may be a good reason to sell. You’re often better off cutting your losses on an investment that’s changed for the worse, instead of putting good money after bad or paying the opportunity cost of keeping your money in an asset that’s no longer attractive.

You think the price will go down

Some investors have a bad habit of trying to time the market and get out of an investment before it dips. Timing the market not only requires you to guess when’s the right time sell off your shares, but also to guess when’s the right time buy back in. This rarely works out well – It often results in selling off your shares too early, or getting back in at a bad price.

The biggest investing mistake I’ve made was trying to time the market. I’ve had many great investments that I sold because I was sure a crash was just around the corner, only to see them continue to climb 2x or 3x (one is now 5x) with no crash in sight. Timing the market is a fool’s game. If you own great companies, hold onto them. Great companies will survive crashes anyway (and usually come out even stronger).

Money Bren

What if you feel that a company’s share price will go down because it’s overvalued? For example, a company you own has a share price of $20, but you feel the shares are only worth $15. We think value alone is an unreliable indicator of when to sell. Whether or not a company is under or overvalued is based purely on an estimate of how much a company is really worth – There’s no way to know with 100% certainty that your valuation of a company is correct, and there could be genuine reasons (that you haven’t factored in) that help justify the company’s high share price.

Further Reading:

– Does timing the market = better returns?

To take profits

Selling off your investments to realise your gains isn’t a bad thing, but we believe that taking profits alone isn’t a good reason to sell. Instead your decision to sell should tie in to whether your objectives for an investment have been met or not. For example, you might be a trader and bought an investment with the objective of selling it at a specific target price – In that case you’d have good reason to sell and take profits assuming that target price had been met.

However, most long-term investors buy with the intention to hold a quality company or fund for several year/decades, instead of regularly selling to take profits. They hold onto quality assets and let their returns compound, and likely avoid capital gains tax in the process. In this case you wouldn’t sell to take profits unless your investment’s fundamentals had changed in a way that made it no longer attractive to continue owning that investment, if your personal circumstances had changed, or to rebalance your portfolio.

Boredom/poor performance

Investments don’t rise in a straight line – Instead there’s times your investments will perform well, and times where your investments will be flat or be performing poorly. These times of poor performance can lead to boredom, and perhaps wanting to sell off your investment in favour of more exciting assets that have been doing better over the short-term.

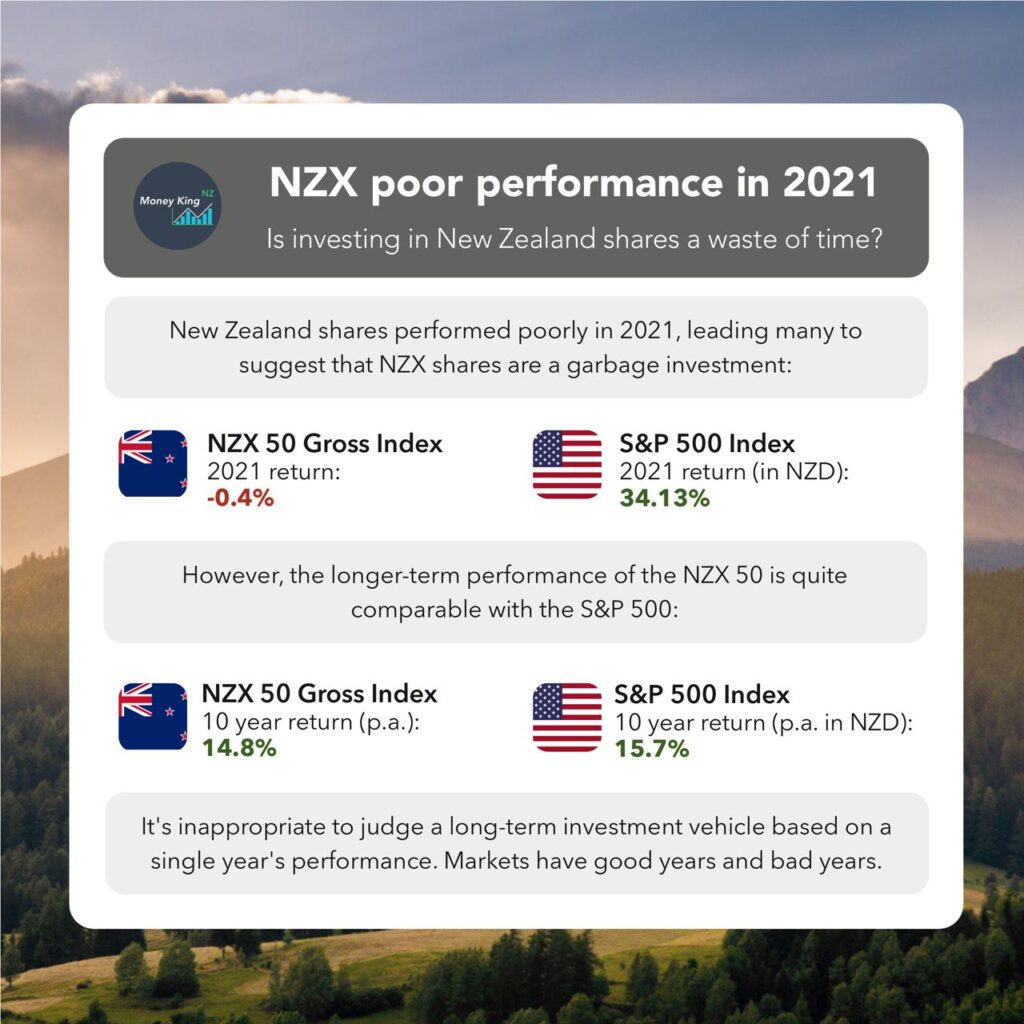

But a stagnant share price doesn’t necessarily mean you’ve got a bad investment. It’s inappropriate to judge a long-term investment based on short-term performance. Take NZ shares for example which haven’t done well in recent years – Over the long-term they’ve been one of the better performing markets globally. So assuming your investment’s fundamentals and your goals haven’t changed, you probably shouldn’t sell. In investing, boring is often best. It’s not a get rich quick scheme, and tends to reward those who are the most patient.

To pay for an unexpected expense

An investment account isn’t a substitute for a bank account. Relying on it to pay for an unexpected expense (like dentist, or car repair bills) potentially comes with the following issues:

- You may be forced to sell your investment at a loss or at a bad price, if the price of your assets have dipped.

- Your investments might not have made enough profit yet, to break even on the brokerage and foreign exchange fees.

- You may have issues being able to sell at all, if the asset you’re trying to sell is illiquid.

That’s why having an emergency fund (held somewhere reasonably accessible like a bank savings account) is so important, as it allows you to cover unexpected expenses without having to disturb your long-term investments.

2. When should you switch funds?

In recent times Kiwis have become more engaged around which KiwiSaver and investment funds are best suited for them, and as a result are increasingly looking to switch to better funds. But knowing when’s a good time to switch from one fund to another is another tricky topic. Let’s take a look at a few scenarios:

Switching between similar types of fund

Example: Switching from one growth fund to another provider’s growth fund

Good reasons to switch

There’s many reasons why you might switch from one provider to another. They might have a better product, better service, lower fees, or invest in things that are better aligned with your ethics.

Bad reasons to switch

It’s a not so good idea to switch to another provider purely based on its past performance. While it can be a good indicator of a fund manager’s quality, chasing performance doesn’t work because a couple of years of great results doesn’t guarantee a fund will continue to perform well into the future. One year’s winners often end up being next year’s losers.

Is now a bad time to switch?

There’s a common misconception that it’s a bad time to switch when the markets are down. In reality there’s no good or bad time to switch between two similar funds. Let’s say you want to switch from one growth fund to another – Despite selling out of your old fund at a loss, all growth funds would’ve been hit by a market downturn, and you’d also be buying back into your new fund at lower prices.

Think of it as moving house during a housing market downturn – You may have to sell your old house at a loss, but you’d also be buying back in to the same market where other houses would also be cheaper due to the downturn.

Switching to a more conservative fund

Example: Switching from a growth fund to a conservative fund

Good reasons to switch

A good reason to switch to a more conservative fund is due to a change to your goals or personal circumstances. For example, as you get closer to your investment goals (like retirement), you might switch from a Growth Fund to a Balanced Fund to take some risk off the table and reduce the volatility of your retirement savings. Alternatively you may feel like your fund’s volatility is causing sleepless nights, so as a result you may switch to a less volatile fund.

Bad reasons to switch

Bad reasons to switch to a more conservative fund include:

- If the price of your fund goes down – You could be locking in your losses by switching from shares to more conservative investments, plus you’ll miss out on the gains when sharemarkets eventually bounce back.

- Trying to time the market – Some people try to switch to a more conservative fund in an attempt to minimise their losses, because they think the sharemarket is going to go down. However, there’s no way to know for sure that the market is going down – And by minimising your losses you’ll also minimise your gains if the sharemarket continues to go up, or when it rebounds from a downturn.

Switching at a loss

What if you’re in the unfortunate scenario where you’re in a growth fund which is in the red, but you need to use the money soon? Ideally you would’ve switched to a conservative/cash fund as you got closer to the time you needed the money, to protect it from the volatility of the sharemarkets. But given the damage has already been done, what options do you have? You could:

- Take the loss and switch to a more conservative fund to help prevent further losses.

- Leave it in the growth fund and hope it recovers. However, there’s no guarantee it’ll recover in time, so this option may better suit those who have a more flexible timeline for when you need the money.

It’s tricky situation as neither options are ideal. This demonstrates the importance of getting your fund allocation right in the first place.

Switching to a more aggressive fund

Example: Switching from a Balanced fund to an Aggressive fund

Moving to a more aggressive fund involves going to more growth assets like shares, so this is more like a decision to buy, rather than one to sell. There’s no such thing as a “good” or “bad” time to switch to a more aggressive fund, as long as you’re doing so because the fund better aligns with your goals or personal circumstances.

3. Tools, strategies, and considerations when selling your investments

There’s a few different tools, strategies, and other things you might want to consider when it comes time to sell down your investments:

Liquidity

Simply put liquidity refers to how easily you can sell an investment for cash. Some investments are very illiquid and are hard to sell:

- KiwiSaver – Can only be withdrawn in certain situations like for buying your first home or when you reach age 65.

- Many unlisted companies – Companies that aren’t listed on a sharemarket, like those purchased through an equity crowdfunding campaign. There often isn’t a way to sell these companies unless it gets acquired by another company, or eventually lists on a market.

- Some listed companies – Even listed companies (especially some very small companies on the NZX) can be illiquid, as there’s often few people wanting to trade the shares of those companies.

So before getting into an investment in the first place it’s important to consider its liquidity, in order to avoid issues down the line and make getting your money out of your investment as smooth as possible.

Lump sum vs Regular withdrawals

When buying investments people often drip feed or “dollar-cost average” into an asset, as opposed to investing a lump sum. Drip feeding spreads your entry into an investment over a period of time, so you don’t have to think about what’s the perfect time to buy an asset or worry about investing all your money at a bad price.

The same concept could be applied to selling your investments, where you could apply the reverse of dollar-cost averaging, by selling off portions of your investment over a period of time. This could help alleviate any worries about the price of your investment continuing to rise after you sell it. Unfortunately few investment platforms offer regular withdrawals (mainly fund managers like Milford or ANZ), so you may have to manually make regular sell orders.

The bucket approach

Let’s say you retire and need to sell down your investments to fund your retirement. Chances are you don’t need all of that money at once, but will be using your retirement nest egg over a period of 30+ years. In this case neither of these investment products would be suitable for you:

- Growth/Aggressive funds – These funds are highly volatile as they’re mainly invested in shares. As a result during a market downturn you could end up having to draw down on your fund at a loss or at bad prices.

- Balanced funds – Even though these funds are split between shares and bonds, the volatility of shares will still pull down the value of the entire fund during a downturn.

- Conservative/Cash funds – These funds are less volatile, but their high concentration towards bonds and cash means you’ll be leaving potential returns on the table given some of your money won’t be spent until 20-30 years later.

The solution is to split your retirement nest egg into different buckets. As an example we could have three buckets, each containing a different investment:

- Bucket 1: Cash – For money you need immediately or in the short-term.

- Bucket 2: Conservative/Balanced Fund – For money you’ll need in the next few years.

- Bucket 3: Growth/Aggressive Fund – For money you won’t be needing for at least several years.

By having multiple buckets, the money you need immediately or in the near future is held in conservative assets, protected from the volatility of the sharemarket. And the money you won’t be needing for a while is sitting primarily in shares, with the potential to generate higher returns over the long-term. Platforms like InvestNow, Flint, and SuperLife all allow you to invest in a customised mix of different funds, so would be suitable for the bucket approach.

Target date funds

These funds automatically allocate you to an investment portfolio based on your age. They work on the assumption that you want to retire at age 65 – therefore younger people start off with an investment portfolio mostly allocated to shares, and have their shares gradually sold down and reallocated towards bonds and cash as they get older.

These funds are a great tool for those who don’t want to manually rebalance their portfolios or switch funds as time passes. However, a big limitation of these funds is that they’re only suitable if you intend to retire at age 65. They won’t work for other investment goals you might have, like if you’re investing to buy your first home or to retire early.

SuperLife, ANZ, and Fisher Funds are examples of fund managers who offer target date funds.

Living off dividend & interest income

Some investors may opt for a strategy of investing into dividend paying companies as well as bonds or P2P Lending to fund their retirement. They could allow you to live off dividend and interest income from your investments, instead of having to sell and eat into your capital. This isn’t a bad strategy as it provides a passive and mostly predictable stream of income, but can come with the following issues:

- It may require you to have more money invested, than if you were planning to eat into your capital.

- Dividend and bond interest payments tend to be infrequent, usually paid every 6 months or quarterly, requiring you to budget well.

- It may result in you wanting to concentrate your portfolio towards high dividend paying companies. This concentration could encourage investing in higher risk companies, sacrificing capital gains, or result in a lack of portfolio diversification.

- Dividends are far from guaranteed. A company can reduce or completely cut them at any time.

- Dividends and interest tend to be taxed less efficiently than capital gains.

Lifetime Retirement Income Fund

The Lifetime Retirement Income Fund is a fund designed for retirees to draw an income out of their nest egg. It invests your money into a balanced fund and pays out an income every fortnight, calculated based on the fund’s projected returns and your life expectancy, with the aim of ensuring your savings don’t run out during your lifetime. The fund provides another handy option for automatically drawing down your investments, but comes with relatively high management fees at 1.35% p.a.

Conclusion

The most important takeaway from the article is to let your goals drive your decisions on whether to sell or switch an investment, rather than market movements. Selling based on price alone often results in letting go of your investments at bad prices, or leaving further growth on the table. Instead ask yourself whether your investment still contributes to your goals, aligns with your personal circumstances, or whether the reasons you bought the investment still apply. Generally if your goals or the fundamentals of your investments haven’t changed, nor should your investments.

Follow Money King NZ

Join over 7,500 subscribers for more investing content:

Disclaimer

The content of this article is based on Money King NZ’s opinion and should not be considered financial advice. The information should never be used without first assessing your own personal and financial situation, and conducting your own research. You may wish to consult with an authorised financial adviser before making any investment decisions.