If you’re a New Zealander you likely intend to buy a house at some point in your life, if you don’t already own one. Housing is more unaffordable than ever, yet it remains an obsessively desired, hyped up possession among society. This article explores a few topics surrounding home ownership. How does your house fit into your investment portfolio? Is it the best way to build wealth? Should you pay off your mortgage or invest? And does buying a house live up to the hype?

This article covers:

1. What’s the role of your house?

2. Buying a House vs Rent & Invest comparison

3. Pay off the mortgage or invest?

1. What’s the role of your house?

What benefits does buying your own house provide over renting one?

Non-financial benefits:

- Stability – You have a stable place to live without the potential threat of a landlord asking you to move out.

- Control – You can customise and use your house however you want, potentially increasing the enjoyment you derive from it. You can knock down walls, repaint your bedroom, and live with no restrictions on owning pets.

- Forced savings – Having a mortgage requires you to contribute a decent chunk of your income towards equity in your house every payday. It forces you to build your wealth, instead of splashing out on other things.

- Symbol of success – Owning a house is often seen as a symbol of financial achievement and success, while renting is often perceived as a waste of money.

Financial returns:

- Capital growth – House (and land) prices grow over the long-term, so you’ll potentially be able to sell your house at a higher price than what you bought it at. And in the likely case you take out a mortgage to buy a house, the leverage will magnify the capital gains you make.

Other benefits:

- Rent – You don’t have to pay rent if you own your own house, but this is a cost saving rather than a true financial return.

So overall there’s a very strong case for buying a house. However, there’s a few issues which are often forgotten when people FOMO into the housing market:

Issue 1 – Renting isn’t dead money

“Renting is dead money. You’re just paying off the landlord’s mortgage.”

The perception that rent is a waste of money is a common argument for buying a house. While it’s true that some of the rent you pay will go towards the landlord’s mortgage, it’s not dead money. Instead it represents the exchange of money for shelter – just like how many of you pay KFC in exchange for fried chicken (instead of raising and cooking your own chickens), or exchange money for electricity (instead of generating it yourself). Yet bizarrely nobody calls paying for food or electricity “dead money”.

Issue 2 – The housing game is a money sink

“I sold a $500,000 house for $1 million, making a massive 100% profit.”

We hear plenty of stories in the news about people making incredible returns from housing. But when you sell a $500,000 house for $1 million, it’s incorrect to say that you made a 100% profit. There’s plenty of ongoing expenses associated with owning a house including:

- Mortgage interest

- Maintenance

- Rates

- Insurance

- Body corp fees (for some housing developments)

Then you have transactional costs associated with buying and selling houses. Chances are you’ll have the desire to climb the “property ladder”, continually upgrading to bigger and better houses, incurring these costs several times throughout your life:

- Real estate agent fees

- Legal fees

- Due diligence costs (e.g. builder’s reports)

That’s a lot of money eaten up by these expenses, bringing a seemingly incredible return right back down to earth. It almost seems as though the housing market serves to line the pockets of agents and banks, rather than homeowners! Lastly, don’t forget the non-financial costs of owning a house such as:

- Time spent on searching for properties, going to open homes and doing due diligence

- Trips to Bunnings or Mitre 10

- Time spent doing maintenance

- Appointments with banks/brokers, lawyers, and agents

Issue 3 – Your house doesn’t provide cash flow

“A house will provide me with a comfortable rent and mortgage free retirement.”

Owning a house outright means you can save tons of money by not having to pay rent or a mortgage. But this might not be enough to realise your financial goals like having the means to fund your retirement:

- Your house locks up your capital. Your house can’t be used to buy groceries or pay for electricity. And you can’t sell off parts of your house to fund a holiday or a new car. You’d have to downsize or take out an expensive reverse mortgage to release this capital.

- Your house doesn’t provide the cash flow needed to pay the bills. It doesn’t generate regular dividends or interest payments like shares and bonds. You’d have to rent out a room if you want to generate income from your house.

- It’s dangerous to rely on Superannuation payments from the government as your retirement income. These might not be enough to fund your desired lifestyle, or the rules on who’s eligible might change by the time you’re retired.

- You KiwiSaver might not get you far either as your account might not be as large as expected. This is especially true if you withdrew some money for your first home deposit, and is compounded by the fact that you may have switched your KiwiSaver to a conservative fund in the years prior to your house purchase.

Role in your portfolio

Your house is more of a lifestyle asset, representing the allocation of capital towards your own means of shelter, rather than a true financial investment. While you can expect it to grow in value over time, it doesn’t possess the same characteristics as true investments like shares. It sucks money from your wallet rather than bringing in cash flow, and you can’t use it to put food on the table. Therefore we wouldn’t consider a house as part of an investment portfolio alongside your shares, bonds, and funds.

Investment properties are different though, bringing in money in the form of rental income. But that’s a topic for another article. We’ll be concentrating on owner-occupied houses here.

Further Reading:

– Property vs Shares – The pros and cons of buying residential property

2. Buying a House vs Rent & Invest comparison

Now that we’ve covered some of the benefits and flaws of buying a house, let’s do a financial comparison between buying a house versus renting and investing.

Scenario A – Nathan from Napier buys a house

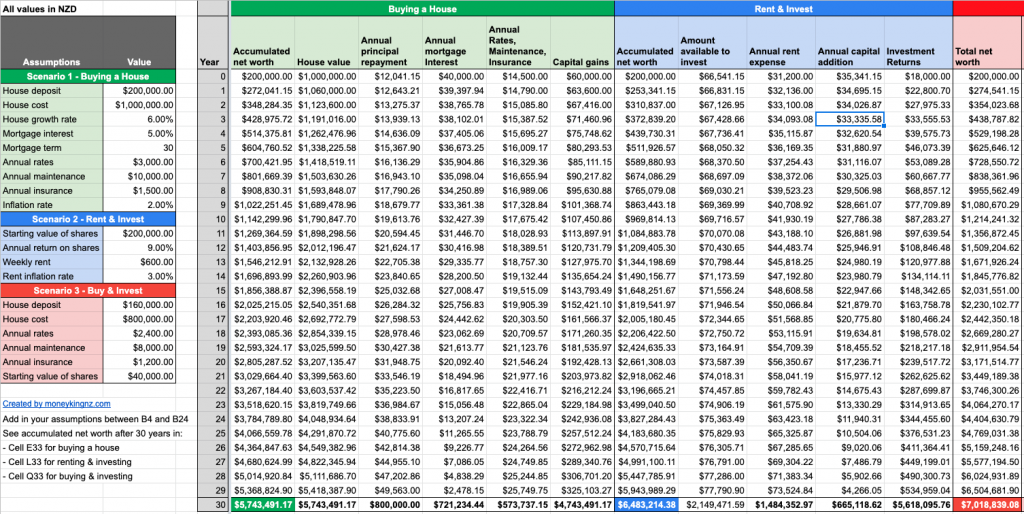

Nathan from Napier has $200,000 to start his journey to build his wealth. He decides to use that money as a 20% deposit on a $1 million house. Let’s assume that:

- He pays the mortgage off over 30 years at an interest rate of 5%. This requires $52,041 per year in principal and interest repayments.

- His house grows at a rate of 6% per year (the rough long-term average).

- In his first year his expenses are $10,000 on maintenance, $3,000 on rates, and $1,500 on insurance. Due to inflation these increase by 2% each year.

At the end of the 30 years, Nathan’s net worth is $5,743,491.

This comprises $1,000,000 capital invested + $4,743,491 of capital gains. Nathan should be stoked! However he also had to pay $761,234 in interest and $588,237 in expenses, so his overall profit is just $3,394,020.

Scenario B – Owen from Oamaru rents and invests

Owen from Oamaru also has $200,000. He decides against buying a house and instead invests in a portfolio of shares.

To keep this comparison fair, the amount Owen contributes to his share portfolio will equal the amount Nathan from Napier puts towards on his house (mortgage payments plus expenses), minus any rent Owen has to pay (given he still needs a place to live!). Therefore our assumptions are:

- He has $52,041 (money that would have otherwise gone to mortgage payments), plus $14,500 (money that would have otherwise gone to rates, maintenance, and insurance) to invest each year (for a total of $66,541).

- He has to pay rent of $600 per week or $31,200 per year. This increases at a rate of 3% per year.

- This results in a total of $35,341 ($66,541 minus $31,200) for Owen to invest in the first year.

- He invests in a portfolio of shares which increases by 9% each year after fees and tax (the rough long-term average).

At the end of the 30 years, Owen’s net worth is $6,483,214.

Scenario C – Penny from Porirua does both

Lastly, we can also explore a third scenario which delivers the best of both worlds. Penny from Porirua approaches things a bit differently. She also starts with $200,000 but instead of buying the most expensive house she can afford, she decides to buy a cheaper $800,000 house with a $160,000 deposit and uses her remaining $40,000 to invest in shares. Let’s assume:

- She has a 30 year mortgage at a rate at 5%.

- Her mortgage payments are smaller at $41,633 per year vs $52,041 for Nathan’s mortgage payments. She invests the $10,408 in savings each year into her share portfolio.

- Her expenses are also 20% cheaper at $11,600 for the first year vs $14,500 for Nathan’s expenses. She invests the $2,900 in savings each year into shares.

- Her shares deliver the same 9% return as Owen’s portfolio.

At the end of the 30 years, Penny’s assets are worth $4,594,793 (her house) + $2,424,046 (her shares) for a total net worth of $7,018,839.

While her house might be smaller or in a worse location than Nathan’s, Penny’s expenses and mortgage payments have been much lower. She’s saved $144,246 in interest, $114,747 in expenses, and has had $160,000 less capital going towards her house – all of which has gone towards building her share portfolio.

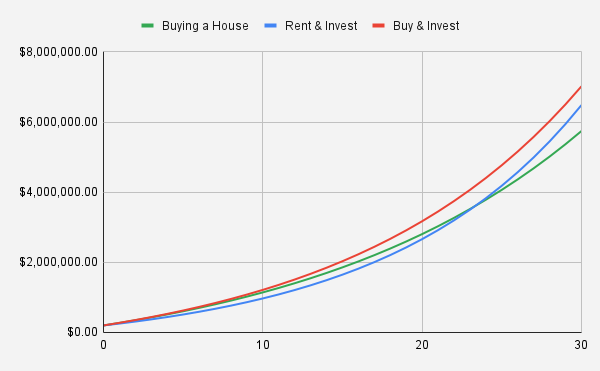

Results

Our three investors all started out with $200,000. They all subsequently spent an additional $2,149,472 over 30 years:

- Nathan – $800,000 on house principal repayments, $761,234 on interest, and $588,237 on expenses.

- Owen – $665,119 on his share portfolio, and $1,484,353 on rent.

- Penny – $640,000 on house principal repayments, $608,988 on interest, $470,590 on expenses, and $429,894 on her share portfolio.

While we all scenarios have delivered a good result for our investors, Penny who bought a cheaper house and invested the savings into shares has come out better off (with $7.02 million), followed by Owen who stayed as a renter (with $6.48 million). However, Nathan is not far behind (with $5.74 million) despite houses having a lower rate of return than shares – in fact he’s ahead of Owen in the earlier years, given the leverage on his house means he’s also making capital gains off the money he’s borrowed from the bank.

Going beyond those 30 years, you could argue that Owen could get left behind as he’s still burdened by having to pay rent. But he could simply buy the same house as Nathan or Penny and even have some spare change left over. On the other hand, Nathan has an asset that can’t be used to put food on the table, unless he sells it, gets flatmates, or borrows against it.

Limitations

- Assumes you don’t use the house to make further returns – Nathan and Penny could have taken on flatmates, leveraged their houses to buy a rental property, or refurbished/extended their houses to further increase its value. This could tilt this comparison in favour of buying a house.

- Assumes you don’t change houses – In reality Nathan and Penny might have moved up the property ladder or moved to another house (e.g. for a new job), potentially multiple times during a 30 year span. This would have cost them real estate agent fees, fees for performing due diligence on their new houses, and legal fees, tilting this comparison in favour of renting.

- Assumes Owen and Penny are disciplined enough to invest their savings consistently – In reality they might be tempted to blow their excess cash on other things, particularly in Owen’s case as he doesn’t have the forced payments that come with a house and mortgage.

- There’s lots of other variables – House and share prices are totally unpredictable and might not grow as expected in the next 30 years. Mortgage rates and expenses can also be volatile. Our calculations are quite basic, and there are so many variables that can throw off the outcomes of our three scenarios.

- It’s hard to quantify the non-financial benefits – While Owen is financially better off than Nathan by renting, he would have missed out on the non-financial benefits that Nathan and Penny enjoyed – like having a greater sense of security and being able to customise their house. These benefits are hard to quantify and will vary from person to person – Owen might have been perfectly content as a renter, not having to deal with the hassles of maintaining and financing a house, not having to commit so much capital towards a single asset, and being able to move more freely. There are downsides to home ownership as well – Penny might be discontent with her longer commute after buying a house in a cheaper location, and Nathan might not enjoy his regular trips to Bunnings.

You can copy the spreadsheet we used to do the calculations here and play around with the assumptions if you wish to do your own comparison.

3. Pay off the mortgage or invest?

The last concept we want to explore in this article is an age old question homeowners face. If you have spare cash, should you use it to pay off the mortgage or invest? An alternative scenario is whether you should withdraw your KiwiSaver money for a larger deposit (effectively reducing your mortgage) or keep it invested for your retirement?

From a financial point of view, the answer comes down to maths. For example, if your investment portfolio of shares is delivering an after tax return of 9% per annum, and your mortgage interest rate is 5%, you’re financially better of investing any excess money. Let’s look at a couple of scenarios to compare:

Scenario D – Quentin from Queenstown pays off the mortgage

Quentin from Queenstown wants to buy a $1,000,000 house and has a $200,000 deposit. He also has $50,000 that he could withdraw from his KiwiSaver. He chooses to put this KiwiSaver money on his house, effectively reducing his mortgage by $50,000.

Assuming a 30 year mortgage at a rate of 5%, he’d cut his mortgage payments by $3,253 each year (saving a total of $97,590 over 30 years). If those $3,253 in savings were invested in shares each year he’d have a portfolio worth $486,504 after 30 years, assuming a 9% return. Not a bad result from putting that $50k towards the mortgage!

Scenario E – Rebecca from Rotorua invests her extra money

Rebecca from Rotorua is in the exact same position as Quentin. But instead she keeps the $50,000 in her KiwiSaver account. After 30 years, that $50,000 would have grown to $663,384 assuming the same 9% return. An even better result!

Limitations

The pay of mortgage vs invest decision will never be a purely financial decision. There’s plenty of non-financial factors to consider such as:

Reasons to pay off the mortgage:

- Your mortgage can be a burden, having such a big mountain of debt to pay off each payday. Paying it off sooner can ease the burden it has on you.

- Investing in shares involves risk and might not deliver the returns you expected, while paying off the mortgage delivers guaranteed returns in the form of reduced interest costs.

Reasons to invest:

- Investing in shares allows you to diversify your net worth away from being concentrated on your house. Especially as buying a house also involves risk, and isn’t a sure thing in building your wealth.

- Investing in shares is an underrated skill. You can pass this knowledge onto your children, nieces, and nephews so they can get a head start on investing towards buying their own houses.

Conclusion

Buying a house isn’t cheap, but the stability it provides for yourself and your family will be worth it for many people. It’s also a solid way to build your wealth. But buying a house isn’t the only way to get rich, and concentrating on your house as your sole means to achieve financial stability and meaningful wealth is a flawed strategy. It’s primarily a lifestyle asset with the role of providing shelter, and it won’t provide you the cashflow you need to pay your bills. Nor are the costs of home ownership cheap – rates, maintenance, insurance, and transactional costs are substantial, and the time you need to take in searching for, purchasing, and maintaining a house is also significant.

On the other hand shares are an underrated asset class, possessing a unique set of properties that you won’t get with a house. Your money invested in shares can be diversified globally across many industries, and can work to grow your net worth without the cost and effort associated with home ownership. When it comes to funding your retirement, a dream car, or holiday, you can easily use the dividends or sell off parts of your portfolio to do so. So as home ownership rates decline nationwide we should put more emphasis on measuring financial success by overall financial comfort and stability, rather than judging people by the houses they own.

Follow Money King NZ

Join over 7,500 subscribers for more investing content:

Disclaimer

The content of this article is based on Money King NZ’s opinion and should not be considered financial advice. The information should never be used without first assessing your own personal and financial situation, and conducting your own research. You may wish to consult with an authorised financial adviser before making any investment decisions.

Thanks for your blog, nice to read. Do not stop.

Thank you 🙂

This article was such an eye-opener. There is so much in the background that you usually do not consider the average user. Like the true cost of driving a car, the cost of takeaway eating or owning a house, etc. I have never considered not buying a house, but this made me think.

I’ve tested your spreadsheet with what was my case a couple of years back :

– 50k deposit for a 500k house (10% for first-home buyers)

– 4% growth rate per annum

-7% mortgage interest (it was smaller then, kept with today’s numbers)

– 5k annual rates

– 2k annual maintenance

– 4% inflation rate

For renting

– 7% annual return on the shares

– $500 weekly rent

– 4% rate increase per year

Numbers stack to buying a house 1.6M compared to 1.4M I would say quite close.

It is hard to generalize and depends on the person, location, financials and many, many other things.

I appreciate your input in presenting the other side that I have not considered.