Investment platforms and services that we all use are businesses. They need to charge fees so they can pay their staff, fund their operations, and in most cases make a profit. Therefore fees are an unavoidable part of investing. However, fees can be one of the most confusing aspects of investing. The wide array of fees that platforms charge can feel like a complicated jumble to investors. In this article we explain and provide examples of the most common types of fees so that you can better understand the charges you might be paying.

This article covers:

1. Transaction/brokerage fees

2. Foreign exchange fees

3. Fund management fees

4. Account fees

5. Spreads & Swing pricing

6. Plans

7. Other fees

1. Transaction/brokerage fees

What is it?

Brokerage platforms like Sharesies, Hatch, Stake, and ASB Securities allow you to buy and sell shares and ETFs on various sharemarkets like the NZX, ASX, and NYSE. These platforms charge you a transaction or brokerage fee whenever you make a buy or sell transaction. This fee only applies to the amount you’re buying/selling, not to the value of your entire holdings.

Fund managers (e.g. Kernel, Simplicity, SuperLife, and Milford) generally don’t charge brokerage fees to buy and sell units of their funds. But there are some exceptions to this such as:

- Foundation Series – The fund manager charges a transaction fee to buy and sell certain funds.

- Smartshares – If you buy/sell Smartshares’ ETFs through a broker that charges transaction fees (like Sharesies or ASB Securities), then you will incur these fees when buying or selling Smartshares ETFs.

- Overseas ETFs (such as Vanguard ETFs listed in the US) – These ETFs must be bought and sold through a broker, so will incur the transaction fees of the broker you use.

Examples of transaction/brokerage fees

Transaction/brokerage fees come in lots of different forms, varying between the different platforms. Some platforms have a percentage based fee. For example, Foundation Series charges a 0.50% transaction fee for their Total World and US 500 funds (but not on their Growth and Balanced funds).

Example

Jeremy has $50,000 invested in the Foundation Series Total World Fund. He decides to invest another $10,000 into the fund. A transaction fee of 0.50% applies to this purchase. This transaction fee only applies to the additional $10,000 of units he’s buying – not to the $50,000 he’s already invested.

The fee Jeremy is charged is $10,000 x 0.50% = $50. As a result of this fee, the amount of money that gets invested into his fund is $9,950 ($10,000 minus the $50 fee).

Some platforms charge a percentage based fee, that’s capped at a certain amount. For example, Sharesies charges a 1.9% transaction fee with different maximum charges for each market:

- NZ shares – 1.9%, capped at $25 NZD

- Australian shares – 1.9%, capped at $15 AUD

- US shares – 1.9%, capped at $5 USD

Example

Kayla buys $1,000 worth of Mainfreight shares through Sharesies. Her transaction fee is calculated as 1,000 x 1.9% = $19. This fee falls under the $25 cap for NZ shares, so she’s charged the full $19.

The next day she buys $2,000 worth of Mainfreight shares through Sharesies. Her transaction fee is calculated as 2,000 x 1.9% = $38. However, given the transaction fee is above the cap of $25, Kayla is only charged $25 for the purchase (rather than the full $38).

Some brokerage platforms charge a flat dollar amount for each purchase/sale. Examples are:

- Hatch – $3 USD per transaction

- Stake – $3 USD per transaction

- ASB Securities – $15 for NZX transactions up to $1,000, $30 for NZX transactions up to $10,000

These flat fees can be expensive for smaller transactions (for example, a fee of $3 is significant relative to an investment of just $50), but can be more cost effective for larger transactions.

Example

Peter wants to buy Nike shares through Hatch. He’ll be charged $3 USD for each purchase he makes, regardless of whether he invests $10 or $10,000 per transaction.

Some platforms don’t charge a brokerage fee at all (instead making money through other types of fees). For example, Superhero doesn’t charge brokerage when you buy or sell US shares (however, they still charge brokerage for Aussie shares).

Overall brokerage and transaction fees can be complicated with so many varying pricing models and rules used by different platforms. There really isn’t a definitive best platform, given different pricing structures will suit different people depending on how much you’re investing and how often you’re making transactions. We’d suggest checking out each platform’s pricing pages to get the full details of their brokerage fees, and doing your own calculations to compare how much you’d be charged through each platform.

2. Foreign exchange fees

What is it?

If you want to buy shares/units in overseas based companies or funds, you’ll need to change your money from NZ dollars to the relevant foreign currency. For example, if you wish to buy US shares, as a Kiwi investor you’ll likely have to change your New Zealand dollars to US dollars before you can invest.

In addition, when you sell overseas shares/funds, you’ll need to convert your sale proceeds back to New Zealand dollars before you can withdraw the money to your New Zealand bank account. For example, if you sell shares in Apple, you’ll get US dollars in return. You’ll need to convert these US dollars into NZ dollars if you want to withdraw this cash into your bank account.

In both of these cases, brokerage platforms (like Sharesies, Hatch, Stake, and Superhero) will charge you a foreign exchange fee to facilitate this exchanging of currency.

Examples of foreign exchange fees

Foreign exchange fees are usually percentage based. For example:

Example

Vanessa deposits $100 NZD into Sharesies. She wants to buy US shares so needs to change that $100 NZD into USD. Sharesies charges an FX fee of 0.5%, so she’s left with $99.50 to convert. At a NZD-USD exchange rate of 0.60, Vanessa gets $59.70 USD.

On some platforms the FX fee is hidden. Instead the “fee” comes in the form of a spread (essentially an inferior FX rate). For example, if the NZD-USD exchange rate is 0.60, a platform might give you a rate of 0.59 to buy USD.

Note that the following are examples of investments that don’t incur FX fees, despite them being associated with international assets:

- Australian domiciled funds on InvestNow (like the Vanguard International Shares Select Exclusions Index Fund). In this case the InvestNow platform absorbs the cost of changing your NZ dollars to Australian dollars.

- NZ domiciled funds that invest in overseas shares (e.g. Smartshares US 500 or Kernel Global 100). Investors buy units in these funds using NZ dollars, and the fund takes care of any foreign exchange costs needed to purchase the underlying assets within them.

3. Fund management fees

What is it?

Funds (whether it be an index fund, actively managed fund, KiwiSaver fund, or ETF) are managed by a fund manager. They charge a fund management fee on each of their funds as their main way to make money. In almost all cases fund management fees are percentage based, and the amount you pay is calculated as a percentage of the amount you’ve invested.

Examples of fund management fees

Fund management fees vary widely between fund managers and individual funds. Active fund managers tend to charge higher fees, usually between 0.6% and 2%. Passive/index fund managers tend to charge lower fees, usually between 0.1% and 0.6%. You can check a fund’s Product Disclosure Statement (PDS) to find the management fee applicable to your fund.

As for how fund management fees are actually calculated and charged, here’s some key facts:

- Unlike transaction/brokerage fees, fund management fees aren’t a one-off fee but rather they’re charged on an ongoing basis.

- They’re typically quoted on an annualised basis. For example, if your fund’s management fee is 0.29%, you need to pay 0.29% of your fund’s value every year for as long as you hold the fund.

- The management fee is calculated and applied daily. For example, a management fee of 0.29% spread across 365 days, would result in a daily fee of ~0.0008% per day.

- The fee isn’t an out of pocket fee, meaning you don’t have to deposit any extra money to your fund manager to pay for the fee. Instead the fee is reflected in the unit price or the value of the fund – In other words the value of your fund will reduce by a small amount every day to reflect the management fee.

Let’s see how this applies in an example:

Example

Jane invests $100,000 into Simplicity High Growth Fund, which has a management fee of 0.29%. Let’s assume her fund doesn’t change in value throughout the year. The amount Jane is charged each year is about $10,000 x 0.29% = $29. This charge is reflected in the unit price of her fund. In other words her fund’s value will drop by $29 over the course of the year (approximately 8 cents per day) to account for the fee.

A notable special case is the JUNO KiwiSaver scheme who doesn’t charge percentage based management fees. Instead they charge a flat dollar amount depending on how much money you have invested with them. For example:

- Investing under $5,000: $2.50 per month fee

- Investing $5,000-$15,000: $5 per month fee

- Investing $15,000-$25,000: $8 per month fee

Is cheaper better?

Fund management fees are generally easy to compare between providers, so it’s often tempting for investors to chase the lowest fees. But cheaper isn’t always better – Here’s some examples where the cheapest might not be the best:

- Value for money is more important than getting the cheapest deal. Things like tax efficiency of a fund, a fund manager’s alignment with your ethics, transparency of a fund’s holdings, and other features a fund manager offers could provide extra value worth paying higher fees for.

- In some cases higher management fees are inclusive of other costs (like brokerage and FX), while lower management fees are not. Take the Vanguard S&P 500 ETF for example, which has a 0.03% management fee. Being listed on the US market, buying into this fund would require you to pay brokerage and FX fees. Meanwhile the Kernel S&P 500 Fund invests in the same underlying assets as the Vanguard fund but has a higher management fee at 0.25%. However, there are additional no brokerage and FX fees associated with Kernel’s fund.

- Some might argue that net returns matter more than fees (i.e. it’s worth paying more for a fund that will deliver higher returns). This is true to some extent, but there is a major caveat to trying to pick funds based on performance – How can you know which funds will perform the best into the future? Higher fees and past performance are no guarantees of future returns.

4. Account fees

What is it?

Account fees are charged purely for having an account open with a particular investment provider. Account fees are usually fixed dollar amounts, and the intention of this fee is usually to cover the fixed costs of having you as a customer (such as onboarding, reporting, and customer support costs). This kind of fee is often called an administration fee, platform fee, or member fee.

Examples of account fees

Account fees are usually charged on a monthly basis. Examples are:

- Kernel – Charges a $5 per month (or $60 per year) platform fee if you invest $25,000 or more into their non-KiwiSaver funds. Investments in Kernel’s KiwiSaver funds or Kernel Save don’t count towards this $25,000 threshold.

- SuperLife – Charges a $1 per month (or $12 per year) administration fee for investing in their non-KiwiSaver funds, or $2.50 per month ($30 per year) for investing in SuperLife KiwiSaver.

- Booster KiwiSaver – Charges a $3 per month member fee if you have a balance over $500.

- Generate KiwiSaver – Charges a $3 per month administration fee regardless of your balance.

Example

Steven has $30,000 invested in Kernel KiwiSaver, and $10,000 in Kernel’s non-KiwiSaver funds. He is not charged a platform fee, given his investments in Kernel’s non-KiwiSaver funds total less than $25,000.

Example

Katie invests in the SuperLife KiwiSaver scheme. She is charged a $2.50 per month administration fee regardless of how much she’s invested.

We’re not huge fans of account fees, as being fixed dollar amounts, they can penalise investors who invest smaller amounts. For example, SuperLife KiwiSaver charges $30 per year, regardless of whether you’re investing $100 or $100,000. On a $100 portfolio this fee equates to 30% of the portfolio, while on $100,000 this fee equates to only 0.03% of the portfolio.

Kernel addresses this concern of being unfair to small investors by only applying their fee to larger investors, however their system isn’t perfect either. On an $25,000 portfolio, the platform fee equates to 0.24% of the portfolio, effectively almost doubling your fees to use Kernel when combined with their standard 0.25% fund management fee.

Fortunately account fees are becoming less common in the investment world, with several KiwiSaver providers having removed them over the past few years.

5. Spreads & Swing pricing

What is it?

A fund invests into a range of underlying assets like shares and bonds. So when you invest into a fund, the fund manager has to go buy those underlying assets of the fund on your behalf. Subsequently when you sell your units in a fund, the fund manager has to sell those underlying assets. There’s a cost involved in making these transactions, such as the brokerage and FX fees a fund incurs in buying/selling its underlying assets.

In some cases the costs of transacting in and out of a fund is absorbed by the fund itself (therefore these transactions potentially have a slight drag on your investment’s performance).

But for some funds, a spread gets applied whenever you buy or sell units. A spread essentially means you buy units in a fund at a premium to the unit price, and sell your units at a discount to the unit price.

Swing pricing is a similar concept to spreads. Instead of applying a fixed spread, a fund manager may adjust the unit price of a fund up or down to cover its transaction costs. It can be a little tricky to figure out the exactly how swing pricing is applied to a fund as it can depend on whether a fund has more buy or sell transactions on a given day, and might only apply when the size of a fund’s transactions exceeds a certain threshold.

While spreads and swing pricing may seem like a brokerage fee, it’s important to note that these aren’t used to make money for the fund manager. Instead spreads and swing pricing are credited to the fund you’re buying/selling to cover its transaction costs, and they’re technically aren’t a fee. In other words, they’re mechanisms to ensure a fund’s performance isn’t adversely impacted by the trading activity of its investors.

For example, let’s say large investor makes a large withdrawal from a fund, and this will incur substantial transaction costs for the fund. This investor is charged a spread or has swing pricing applied to compensate the fund for the associated transaction costs, ensuring that other investors in the fund aren’t footing the bill for that investor’s trading activity.

Examples of spreads and swing pricing

Spreads will vary between fund managers, individual funds, and may even vary depending on whether you’re buying or selling into a fund. They typically fall between 0.10% and 0.20%. A few examples of spreads are:

| Fund | Buy spread | Sell spread |

| Foundation Series Balanced Fund | 0.08% | 0.11% |

| Foundation Series Growth Fund | 0.10% | 0.11% |

| Pathfinder Global Water Fund | 0.05% | 0.05% |

| Vanguard Intl. Shares Select Exclusions Index Fund | 0.07% | 0.07% |

| Vault International Bitcoin Fund | 0.25% | 0.25% |

If you’re an InvestNow customer, the platform has a handy page listing the spreads of the various funds they offer.

Example

Shirley is buying units in the Foundation Series Growth Fund. Simeon is selling units in the Foundation Series Growth Fund. The current unit price of the fund is $5.00.

With a buy spread of 0.10%, Shirley buys her units at a price of $5.005 (instead of $5.00). If she’s investing $10,000, this would buy her 1,998 units in the fund.

With a sell spread of 0.11%, Simeon sells his units at a price of $4.9945 (instead of $5.00). If he’s selling 2,000 units in the fund, his sale proceeds would be $9,989.

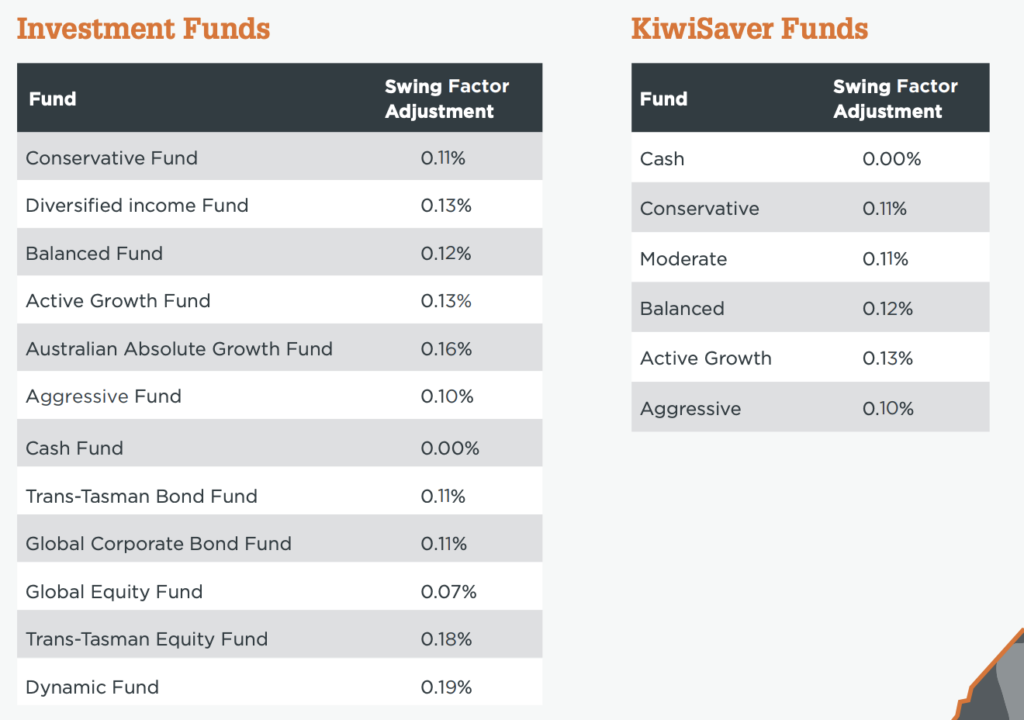

Milford is an example of a fund manager that applies swing pricing to their funds (except for their Cash Fund). The “swing factor adjustment” for their funds ranges from 0.07% to 0.19%. Whether the swing factor adjustment increases or decreases the unit price of the fund depends on the fund’s net flows on a given day. If a fund receives more buy orders than sell orders on a particular day, the fund will have to buy more of its underlying assets, so the unit price will swing up. However, if a fund receives more sell orders than buy orders, the fund will have to sell some of its underlying assets, so the unit price will swing down.

Example

David is buying units in the Milford Aggressive Fund. Today the net inflows to the fund are positive (meaning there is a greater volume of buy orders versus sell orders). Therefore the unit price of the fund swings upwards by the fund’s swing factor adjustment of 0.10%. David effectively buys into the fund at a 0.10% premium.

A week later David buys more units in the Aggressive Fund. Now the net inflows to the fund are negative (meaning there is a greater volume of sell orders versus buy orders). The unit price of the fund swings downwards by the fund’s swing factor adjustment of 0.10%. David effectively buys into the fund at a 0.10% discount.

Kernel is an example of another fund manager that may apply swing pricing to their funds, but is only used at their discretion and only when you make a sell order large enough that it would result in a material cost to the fund:

We may charge “swing pricing” directly to an investor if the investor’s withdrawal request causes what we consider to be material cost to the relevant Fund (and therefore disadvantages other investors). The actual transaction costs attributable to the investor’s withdrawal will be deducted from the amount withdrawn, ordinarily expected to be 0.10% or less of the amount withdrawn. The amount deducted will be credited to the Fund and not to us.

Kernel Product Disclosure Statement

6. Plans

What is it?

Plans are relatively rare. They’re like a monthly subscription fee that you pay to your investment platform. They may seem similar to account fees, but have a couple of key differences:

- Plans are completely optional, whereas account fees are mandatory.

- Plans get you additional features over what an investment platform normally offers (such as reducing other fees you pay or unlocking special features on the investment platform).

Examples of Plans

Sharesies offers a selection of optional monthly plans. Those opting in to a Sharesies plan don’t need to pay transaction fees for up to a certain value of transactions each month:

| Plan | What you’ll get each month |

| $3 plan | Transaction fees covered on up to $500 NZD of individual trades, plus Transaction fees covered on up to $1,000 NZD of auto-invest orders |

| $7 plan | Transaction fees covered on up to $1,000 NZD of individual trades, plus Transaction fees covered on up to $3,000 NZD of auto-invest orders |

| $15 plan | Transaction fees covered on up to $5,000 NZD of individual trades, plus Transaction fees covered on up to $10,000 NZD of auto-invest orders, plus NZX market depth subscription |

| $1 kids plan | Transaction fees covered on up to $500 NZD of individual trades, plus Transaction fees covered on up to $1,000 NZD of auto-invest orders |

So depending on how much money you’re investing each month, subscribing to one of Sharesies’ plans can work out cheaper than paying their standard 1.9% transaction fee.

Example

Greg is subscribed to Sharesies’ $3 monthly plan. This month he is auto-investing $1,000 NZD into his portfolio, plus making a further $750 NZD in buy and sell transactions. Greg doesn’t pay any transaction fees on his $1,000 of auto-invest order, nor does he pay any transaction fees on the first $500 of his additional buy/sell orders, because those transactions are covered under his monthly plan. However, the remaining $250 of his buy/sell orders incurs Sharesies’ standard 1.9% brokerage fee (equalling $4.75), given this transaction amount exceeds his plan’s coverage. Overall Greg pays a total of $7.75 for the months transactions. Without the plan, he’d be paying $33.25 in standard brokerage costs.

Stake also offers a plan under the “Stake Black” brand, which unlocks extra features on the Stake platform. These features include:

- On-platform access to financial statements and data for each company.

- Access to analyst buy/sell ratings and price targets.

- Ability to immediately reinvest unsettled funds.

Stake Black costs $15 NZD per month, and this is discounted to $13 NZD per month if you pay for your plan annually ($156 per year).

7. Other fees

So far in this article we’ve covered the most common types of fees you’ll probably encounter, although there are lots of other types of fees out there. Examples are:

- Performance fees – Charged by some actively managed funds in return for outperforming a certain benchmark like the market index.

- Fees to deposit and withdraw money – It’s uncommon for investment platforms to charge you just for putting in and taking out money, however there’s some exceptions. For example, Sharesies charges a fee for depositing funds using a credit card, Stake charges a 0.50% surcharge for express funding, and Interactive Brokers charges $15 per withdrawal if you make more than one withdrawal per month.

- Tax form fees – A one-off fee charged by some brokers for filing your US tax forms when you first sign up with the platform. Stake charges $5 USD, while Hatch charges $1.50 USD.

- Annual tax filing fees – Charged by some brokers to file your US tax paperwork for your US share investments. Hatch charges $0.50 per year for this.

- Transfer fees – Charged to transfer your shares in or out of a platform. For example, Sharesies charges a $15 fee to transfer your NZ shares out to your CSN, or up to $100 USD to transfer your US shares to/from another broker.

- ADR fees – Charged for holding shares in an American Depositary Receipt (ADR). These fees are typically up to $0.10 USD per unit, per year.

Conclusion

There’s lots of types of fees charged by investment services, but they ultimately boil down to 2-3 categories:

Firstly there are transaction based fees which are only incurred when you perform a certain action:

- Brokerage fees – Charged when you buy or sell assets through a brokerage platform.

- Foreign exchange fees – Charged when you change money from one currency to another.

- Spreads – Applied when you buy or sell units in certain funds, to cover the fund’s costs of buying or selling its underlying assets.

Then there are ongoing fees which get charged for as long as you hold a certain investment or use a particular platform:

- Fund management fees – Charged on an ongoing basis to pay for a fund manager to manage your fund.

- Account fees – Charged on a regular basis to have an account with some platforms/fund managers.

Lastly, some fees are totally optional such as:

- Plans – Gets you additional features over what an investment platform normally offers.

Fees ultimately act as a drag on investment’s performance, given they result in less money working for you and earning a return. It’s understandable that investors want to minimise them. But don’t let analysis paralysis get you – Investors are often better off going for a reasonably priced investment provider over spending weeks/months/years trying to figure out the absolute cheapest option (and perhaps not taking any action at all after getting overwhelmed by the options).

Follow Money King NZ

Join over 7,500 subscribers for more investing content:

Disclaimer

The content of this article is based on Money King NZ’s opinion and should not be considered financial advice. The information should never be used without first assessing your own personal and financial situation, and conducting your own research. You may wish to consult with an authorised financial adviser before making any investment decisions.

Thanks for another great article.

Reading this I was wondering whether simplicity really only has fund management fees. Is this correct. The article only mentions Simplicity twice. First saying that it does not have brokerage fees and a second time saying that it has fund management fees.

That is correct.

Thanks for this content as always…

Have you stopped writing about the monthly “what’s happening in the markets”?

We were on holiday last month and also this month, and there’s not much happening in the market anyway. But hopefully our monthly updates will be back in November.

Biggest investment ‘fee’ most investors will pay is the extremely high and outdated 5% FDR on PIEs, adding a 1.4%pa wealth tax on PIEs. Fingers crossed this will be reviewed with a new government – hoping Andrew Bayly will be looking into this.

Then which index fund is best to save our money? I started with kernel. As of now investing in 3 funds apart from kiwisaver. So they after reaching 25k target for non kiwisaver funds they will charge 60 $ yearly apart from my 3*0.25 funds. Does this 0.25 is every year maganement fees? or it applies for every sell and buy? Please do explain. Then how to save good money for daily wage employee. I have 2k invested