How much money can you make when you invest in shares through an index fund like the S&P 500? Many people suggest that you can make a return of around 10% per year, which is the approximate average return the S&P 500 index has delivered over the past several decades. However, we argue that a 10% p.a. return is an unrealistic result to expect. In this article we’ll cover the reasons why.

This article covers:

1. Why do many investors expect a 10% return?

2. Why a 10% p.a. return is unrealistic

3. Is investing still worth it?

1. Why do many investors expect a 10% return?

The long-term performance of the S&P 500, the world’s most famous and widely followed sharemarket index, is approximately 10% per annum. This leads investors to believe that investing in a S&P 500 or similar index fund, will get you a similar return going forward. Many investing resources seem to support this claim:

Over time indexes have made solid returns, such as the S&P 500’s long-term record of about 10 percent annually. That doesn’t mean index funds make money every year, but over long periods of time that’s been the average return.

[10%] is the average return over the last 20 years! An index fund will get you this.

And we’ve all seen investment influencers push out the following type of content:

If you invest $1,000 per month over 40 years, you’ll end up with $5.3 million assuming a 10% p.a. return.

Sam has a side hustle earning $250 per month. They invest all of that money into an index fund. After 40 years they’ll have $1.3 million.

Sounds pretty good right! A 10% return combined with compounding returns over decades makes investing in an index fund seem like a simple way to accumulate millions of dollars, setting you up for a comfortable retirement.

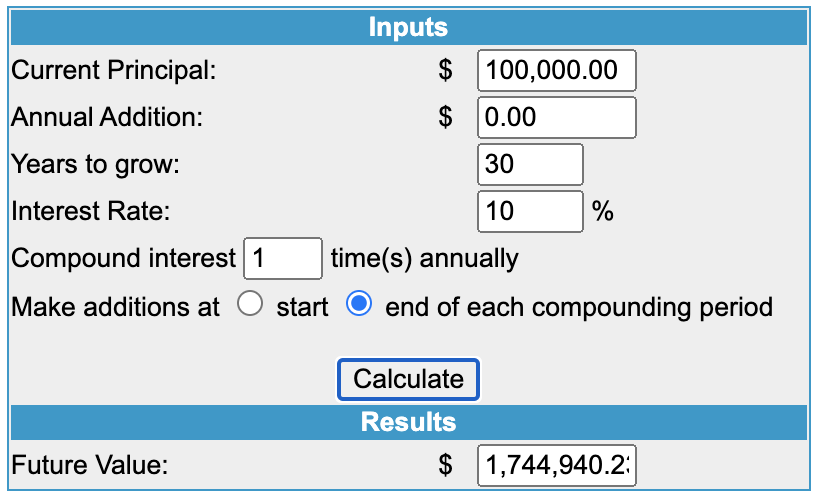

You can plug your own numbers into a compound interest calculator to perform your own calculations. For example, by inputting a $100,000 initially investment, we end up with $1.7 million after 30 years assuming a 10% p.a. return and no further contributions.

But these figures are misleading and paint an unrealistic picture of what returns you could get from investing in shares. Let’s look at the reasons why.

2. Why a 10% p.a. return is unrealistic

A. It ignores emotional factors

People often get caught up in poor investing behaviours that lead to getting a below market return.

Firstly, the 10% p.a. return of the S&P 500 is just an average, and it doesn’t mean you’ll get that return every year. In some years the market will do really well, but in other years the market will perform poorly and perhaps even deliver a negative return. So to get that average 10% return you would have had to navigate volatile and uncertain periods where your investments fall in value. Unfortunately a lot of investors fail to get past this hurdle, becoming fearful of the situation. Bad news (e.g. of recessions, pandemics, politics, wars, and financial crises) and market downturns lead investors to get scared, leading them to try and time the market or perhaps quit investing altogether. That subsequently causes them to miss out on the big gains when the markets rebound.

Secondly, investing is boring, and even more so when investing in index funds. While index funds are relatively safe investments, they don’t provide the fun and excitement of picking and following individual companies, nor do they have the potential to deliver quick gains. This can lead to greed or FOMO over meme stocks, cryptocurrencies, or whatever investment is trendy right now. These tend to be more speculative assets which could work out for you if you get lucky, but are just as likely to hurt you – they’re more like gambling rather than investing. Ultimately they’re not sustainable investments to hold long-term, and investing in these means less money going towards index funds and therefore likely act as a drag on your returns.

So while most investors know in theory that they should simply buy and hold for the long-term, in reality they still fall victim to the emotions that work against their returns.

B. You can’t invest in an index

Even if you’re the perfect investor by not panic selling during market downturns, and by resisting the temptation to dabble in speculative assets, your returns still won’t match the market average. That’s because you can’t invest in an index like the S&P 500. An index is just a hypothetical collection of assets. Essentially it’s just a list of companies. For example, the S&P 500 is pretty much just a list of the 500 largest companies listed in the United States.

You can however invest in an index fund – which tracks an index, or in other words tries to replicate the performance of an index by buying and holding all the underlying companies of the index. For example, an S&P 500 index fund buys and holds the shares of all 500 companies within the index, in order to deliver a very similar return to the S&P 500 index.

There’s a number of important differences between an index and index fund that means an index fund will almost always deliver a below market return:

- Tax – Investments in index funds are taxed, while the performance of indexes don’t factor in any tax.

- Management fees – Index fund managers charge management fees, which is a percentage of the amount you have invested. This usually ranges from 0.03% to around 0.50% (though some funds charge even more!).

- Transaction fees – For many index funds you have to pay transaction fees to buy and sell them. In addition there are foreign exchange fees associated with buying/selling overseas funds. Every dollar going towards these fees is one less dollar invested in the market and making a return for you.

- Brokerage – You fund manager has to pay brokerage fees to buy/sell the underlying assets in an index fund. These costs can act as a drag on your returns and are often passed onto investors in the form of a spread.

- Tracking differences – Index funds often don’t track their index perfectly. Things like the amount of cash an index fund holds cause the return of the fund to be better or worse than the market.

These are quite technical differences, but essentially they mean that even if an index were to deliver a 10% return, as an investor in an index fund your results definitely won’t be as high as that.

C. Past returns doesn’t = future results

This one is so simple, but often forgotten. Just because an index delivered an average 10% p.a. return for the last century, doesn’t mean it’ll deliver the same return going forward. Unlike a term deposit or savings account (where the interest rate is clearly laid out for investors to see), there’s no way to know the exact future returns of the sharemarket unless you had a crystal ball.

D. It assumes you’re fully invested into shares

Say you are investing for retirement at age 65 in 30 years time – it would be incorrect to assume you’d be investing in shares and getting a 10% p.a. return for that entire 30 year span. In reality you’re likely to slowly move to more conservative assets like bonds and cash as you get closer to your retirement goal. And other factors like buying your first home or having a lower risk tolerance might also require you to have an allocation towards lower return assets. As a result your returns will likely start higher, then taper off as you gradually shift from an aggressive investment portfolio to a more conservative one.

E. Inflation

Earning a 10% return on your investments doesn’t necessarily make you 10% wealthier. That’s because of inflation, where the price of goods and services go up over time. A 10% return is likely to be closer to 7-8% when adjusted for inflation, as each dollar becomes less and less powerful over time.

3. Is investing still worth it?

What’s a more reasonable assumption?

We prefer to be a little more conservative when making assumptions around how profitable our share and index fund investments will be. Taking into account fees and tax we’d assume an average annual return of 8% at the very maximum, and even lower if you wanted to account for inflation.

Alternatively we could look at the assumed rates of returns that the government sets for different types of KiwiSaver funds, which are even more conservative than we are. These are standardised rates used by all KiwiSaver providers to project the future balances for their investors. If you invest in an Aggressive fund (which contains close to 100% shares), it’s projected that you’ll get a 5.5% return per year – that’s almost half of the 10% return that many people assume!

So if we revisit the examples we provided in section 1 of this article:

If you invest $1,000 per month over 40 years, you’ll end up with $5.3 million assuming a 10% p.a. return.

- Assuming an 8% return, we’d end up with only $3.1 million

- Assuming a 5.5% return, we’d end up with only $1.6 million

Sam has a side hustle earning $250 per month. They invest all of that money into an index fund. After 40 years they’ll have $1.3 million.

- Assuming an 8% return, we’d end up with only $777,000

- Assuming a 5.5% return, we’d end up with only $410,000

So using our more realistic rates of return, we end up with much less money than what many finance influencers suggest we could have. And that’s before taking into account inflation, and the fact that you’re likely to shift to a more conservative asset mix as you get older. This is important as using the wrong numbers and assumptions could mean getting your retirement planning incorrect, and could make the difference between a great retirement and a mediocre one.

Is investing in shares still worth it?

Investing in shares might not be as fruitful as some people may suggest. But it’s still one of the best ways to grow your wealth. It beats doing nothing with your money and not having it grow at all. In fact, you could consider investing in shares as a necessity in order to protect your money from the effects of inflation over the long-term.

And shares still beat other asset classes like bonds and bank deposits. If you’re investing in Defensive or Conservative funds (which are largely made up of bonds and cash), the government assumed rate of return is only 1.5% or 2.5%:

| Type of fund | Assumed rate of return (after fees and tax) |

| Defensive | 1.5% |

| Conservative | 2.5% |

| Balanced | 3.5% |

| Growth | 4.5% |

| Aggressive | 5.5% |

Even though current bank deposit and bond interest rates seem appealing, remember these asset classes are also subject to factors like tax, and will deliver a less attractive return than shares over the long-term.

Tips to maximise performance

As we’ve seen throughout this article, investing in shares isn’t always as easy as putting your money in an index fund and letting it grow by x% each year. Here’s some important things to consider to improve your results:

- Start early – Starting to invest as early as possible is one of the easiest ways to improve your results. More time in the market means more time for your assets to grow and compound. For example, a 25 year old who invests $1,000 per month for retirement at age 65 would end up with $1.6 million after their 40 years of investing (assuming a 5.5% return). Someone starting at age 35 would need to invest almost double the amount (around $1900 per month) to end up with the same $1.6 million at age 65.

- Watch out for fees – Transaction and management fees mean less of your money going towards your investments to make a return. Ensure that any fees you’re paying provide value for money. For example, a 2% transaction fee might be expensive for an investment that you expect to make a return of 4% per year, given the fee represents half a year of returns.

- Consider tax efficiency – Unfortunately some investments get taxed less efficiently than others. For example, funds that are structured as listed PIEs are taxed at a fixed rate of 28% – not great if you’re investing on behalf of a child. Other funds and products can have varying degrees of tax leakage.

Further Reading:

– Tax on foreign investments – How do FIF and Estate Taxes work?

– What taxes do you need to pay on your investments in New Zealand?

- Ignore the emotions – Your emotions are rarely beneficial when it comes to investing. Checking your portfolio less often, ignoring the headlines, using auto-invest, and staying away from hot tips on social media are things that can help you avoid poor investing behaviours.

However, don’t spend too much time analysing things like fees and tax efficiency. It’s better to just pick a reasonable platform/fund to invest in (even if it isn’t necessarily the best one), instead of letting analysis paralysis hold you back from investing altogether.

Conclusion

Many people commonly assume that investing in shares or an index fund provides an average return of 10% p.a. However, tax and fees alone ensure that trying to match the returns of the market is almost impossible. In addition there’s emotional pitfalls that affect many investors – whether it be panic selling out of the market during a downturn, or trying to outsmart the market by dabbling in speculative assets. So we’re sorry to say that you probably won’t end up with $5.3 million after investing $1,000 per month for 40 years. A more realistic return to expect is likely to be closer to around 5.5% p.a.

This may seem like a party pooper article but we still believe that investing is a great way to get rich, albeit much more slowly than some people suggest. We’re just hoping to provide a more realistic view of investing (e.g. so nobody tries to plan for retirement using unrealistic assumptions), and highlight that there’s other important factors to consider when investing in shares like tax efficiency, minimising fees, and ignoring your own emotions.

Follow Money King NZ

Join over 7,300 subscribers for more investing content:

Disclaimer

The content of this article is based on Money King NZ’s opinion and should not be considered financial advice. The information should never be used without first assessing your own personal and financial situation, and conducting your own research. You may wish to consult with an authorised financial adviser before making any investment decisions.

I personally think this is a really important and really useful article to write. Some of the suggested returns, including by some well known sources, are just silly (Looking at you Dave Ramsay and your 12% return!).

~5% isn’t as exciting, but its soo important that people do have a realistic understanding of what’s likely. $1000 a month for 40 years is only $1.6 million. Still sounds better than putting it off and not investing at all to me!

Thanks for the thoughtful, well written, and comprehensive article (as ever!).

cheers,

Mike

Thanks for your support Mike. Have to admit we were a bit nervous about putting this article out there as it was quite negative compared to what we usually write. But you are spot on – it’s important to address the outrageous returns that so many finance influencers use in their content!

Thanks for a good article which brings a sense of reality to our expectations of returns.

What surprises me is some funds, such as the Milford Active Growth Fund, claims a return of 11.45% since inception on 1st Oct 2007 after fees and before tax. Do you have any explanation for this apparent contradiction to what you have written in your article?

Thanks

George

Hi George, our article’s main focus is on index funds and how it’s unreasonable to expect the market return of 10% p.a. when investing in them.

However Milford is an active fund manager – they research and pick individual shares and bonds to invest in instead of investing in an entire market or an index. With good asset selection they have the potential to outperform the market, which they have done so over the years.

The problem is that most active fund managers fail to be like Milford and outperform the market consistently over the long term and even if they do, their future performance isn’t guaranteed.

I think it also depends on what those returns are from and if those returns are mostly from a few well-picked or lucky picks stocks.

Maybe there were lucky and picked Apple, Meta, or Google/Alphabet very early and coasting on growth from these? Or alternately, they are consistently great at picking the winners and backing them early or early enough. The latter is less likely to be consistently.

Hi Money King,

For 100% long term share holding, I wondered what your view was on the scenario of choosing something with low fees, highest capital gains (given these are not taxed), lowest dividends (given these are taxed).

What are your thoughts on the best fund for this? VT? SNP 500? VUG (growth stocks)?

Many thanks!

Jeremy

Hi Jeremy, tax is a little more complicated than that. In some cases capital gains are effectively taxed – this occurs if you invest over $50k in overseas assets in which case you’ll be taxed under the FIF rules, or if you invest through a NZ domiciled PIE in which case you’ll pay FIF tax indirectly. In those cases choosing gains over dividends has no tax benefit.

From a portfolio construction point of view, concentrating your portfolio on capital growth could result in your portfolio being less diversified or more volatile as you’d have fewer dividend paying companies.

Overall, while tax efficiency is an important consideration, we wouldn’t let it be the main driver of what to invest in. We would argue that adequate diversification and having a portfolio that aligns with your goals are more critical.